Hal McGee

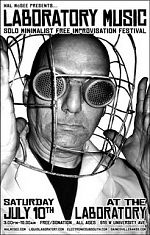

Residing in Gainesville, Florida, Hal McGee has been an essential figure in underground music since the early 1980s working hard with his own music, collaborations and compilations, publications and live performances.

Hal McGee’s dedication to other peoples creative expression is legendary. He has been tireless in championing the work of avant garde artists for decades now. He has done so with compilation tapes like his “Tape Heads” series, his publications like Electronic Cottage and Halzine, his more recent forays into Microcassettes with his Dictaphonia series, and his live performances in which he has now become a mentor figure in his local area.

In September 2010 Hal McGee reissued all of his cassettes from 1982 to 1991.

Also, listen to the album Hal and I made together called “Hoax.”

Residing in Gainesville, Florida, Hal McGee has been an essential figure in underground music since the early 1980s working hard with his own music, collaborations and compilations, publications and live performances.

An early release on Hal and Debbie Jaffe’s Cause And Effect label released on New Years Day 1986. This lo fi chaos mixes radio sounds and squalls of noise into a disturbing and confounding heap.

A collaboration between Hal and Carl Howard released on Carl’s audiofile label in 1990. This tape was more floating and ethereal electronics and keyboards.

Hal McGee’s dedication to other peoples creative expression is legendary. He has been tireless in championing the work of avant garde artists for decades now. He has done so with compilation tapes like his “Tape Heads” series, his publications like Electronic Cottage and Halzine, his more recent forays into Microcassettes with his Dictaphonia series, and his live performances in which he has now become a mentor figure in his local area. Some pictures below of some of these projects.

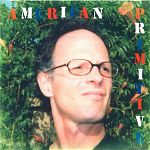

One thing that sets Hal’s music and art apart from other experimentalists is his ability to make his work autobiographical and not being afraid to show the world what and who he is. He has been doing this since the earliest days of Dog As Master, continued in his various tape releases and still maintains a fiercely personal touch. His 2007 CD ( above), “The Man With The Tape Recorder” is a good example of this.

Hal also has a fine eye for visual design and expression as well. His colorful CD covers explode with life. Above, his compilation “Space Exploration”

Hal uses keyboards, electronic devices, theremin, effects, found sounds, pre-recorded tapes, microcassettes, field recordings and much more to create his work. Below, two collaborations. The first is one of my favorite collabs with Charles Rice Goff III called “Verve Of The Void”. A spacy, minimal, keyboard excursion that is truly sublime and seamless.

The second, a collab with Brian Noring, “Fortuitous Happenstance” that combines field recordings, keyboards and mystery sounds into an engaging aural trip.

Another of my favorite Hal collaborations was with Al Margolis and released on Al’s Sound Of Pig label in the mid 1980s. This tape, “Untranslatable” veers off road into keyboard, percussion and odd sounds. Not harsh but also not easy listening or ambient.

Electronic musician and the proprietor of the Harsh Reality Music label from Memphis, Chris Phinney appeared on the cover of EC #2 in 1989.

Involved with the Generations Unlimited label with Gen Ken Montgomery and also a key player in the early home recording electronic music scene, Dave Prescott was featured in EC #3.

I appeared on the cover of EC #5 in 1991. I remember taking this picture outside of the small apartment in San Jose I lived in for a couple of years in the early 90s.

Hal included full sized (8.5×11 ) pages with many of his mid 90s releases. The one above is a collaboration from 1996 with Brian Noring from Des Moines.

This 1997 tape featured Big City Orchestra reacting to some Hal material on one side and Hal reacting to their sonic investigations on the other.

Hal released a tape by 360 Sound in 1997 called, “Tofu And Tobacco”. 360 Sound was the project of Brian Noring and Shawn Kerby here joined by Brian’s wife, Kathy and Hal.

In 1997 Hal traveled to Des Moines to visit and jam with Brian Noring, Charles Rice Goff III, Shawn Kerby and Phillip Klampe. This session produced several recordings released not only by Hal but Goff and Noring as well.

In 1998 Charles Goff did the traveling and visited Hal in Florida to record this cassette of spooky keyboards and weird sounds.

The year of release is not listed on the credits of this release but it appears to be about 1997 or 1998 I’d say and is actually an outing by Al Margolis’ project, If,Bwana. I do not believe Hal appears on this cassette. Front image above, back image below.

Halzine #1 appeared in 1997 with Brian Noring and wife Kathy on the cover. Halzine was a more personal publication than Electronic Cottage detailing Hal’s concern’s peppered with underground information.

Yet another project devoted to international sound making, “Quotidian Assemblages” was a series of CDs based upon ordinary everyday sounds by a myriad of international artists such as GX Jupitter-Larsen, My Fun, Ernesto Diaz-Infante, EHI, Jeph Jerman, Charles Goff and many others. The first volume came out in 2003.

For awhile Hal was very involved in the Tape Germ collective, a web site run by Bryan Baker and Chris Phinney devoted to loops and the remixing, re-arranging, adding to, and then uploading back to, web site. I always felt that Hal’s approach was very unique utilizing the loops in an entirely different way than others and once again, making personal statements. His first volume of these works arrived in 2005.

Another aspect of Hal’s art was his solo piano work. On this 2004 collaboration with Albert Casais on guitar, he plays a relatively straight forward, non affected, keyboard, probing in an almost Stockhausen style. He also released solo piano albums in this vein.

Using a large arsenal of electronic instruments, Hal and Dave Fuglewicz churn out two extended, long form collaborations that swirl and swerve. Released in the early 2000’s I believe. Dave has also been a very prolific electronic music maker, collaborator and member of The Tape Germ Collective.

Hal’s solo music has often been a push-pull, diametric of modern versus primitive. On some CDs below you will see the artistic influence perhaps of such artists as Jean DuBuffet, Willem DeKooning, Kurt Schwitters and others. Art work on this release by Marcel Herms. “Orion The Hunter” from 2005.

From 2000, “Wired For Sound” continued Hal’s tradition of incorporating field recordings from his daily life into the proceedings taking it to even more intimate private moments. A real classic of 21st century Hal McGee.

The past few years have seen an increased involvement with his local scene in Gainesville. Florida where he has assumed “wise teacher” status to a crowd of younger, probing artists. This CD from 2007 has him in the company of locals musicians Brandon Abell, Jennifer Abell, Jay Peele and Chris Page.

Above, a sampler of 58 tracks ( blended into one continuous piece) from Hal’s “Sampler #1” that spans the years 1981-1991.

Above, some albums with Chris Phinney from the 2000’s. I particularly like these electronic voyages and the cover art is sumptuous, colorful and expressive.

In addition to publishing his Electronic Cottage Magazine, Hal also produced 3 compilation tapes to go with them . Some of the artists on this volume: Mike Hovancsek, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Keeler, Darren Copeland, Rendezvous Debris, Abner Malaty, Dimthingshine and others.

Venturing back into the world of cassettes, Hal made this short tape in 2008 of autobiographical insights with his two dogs on the cover.

In 1988 Hal teamed up with another underground electronic music giant, Dave Prescott for this tape on Harsh Reality Music

Going back to 1988 this tape by Hal McGee, “Devices And Mechanisms” was released on Mike Crooker’s GGE label from Ohio.

In your early experiences comments for this site you said you first got involved with the home taper scene in about 1981, introduced by Debbie Jaffe and Rick Karcasheff. Were you already recording your own music? Were you also involved in the mail art scene then?

I had been involved with a couple of bands in Indianapolis.

The first was in the late 1970s and was called Medusa. It consisted of me on vocals, my brother Mark on drums, a neighbor, Rickey H, on guitar, and a guy named Ronnie K on guitar. We played two chord rock songs that were a cross between the Sex Pistols and Alice Cooper. I remember that we actually wrote one song called “We’re So Bored”. We played one show at a birthday party for a teenage kid and I remember that I felt compelled to change the word “damn” to “darn” in the refrain of “We’re So Bored”.

The second band was called Purely Physical and was centered around three students from the Herron School of Art in downtown Indianapolis: Joe M on guitar and vocals, Brett K on guitar and vocals, Charly K on bass, and Mark McGee on drums. They had an edgy, nervous guitar sound that I described at the time as “terse, taut, and tight”, or something like that. At first I was just associated with the band in an advisory role of sorts. Later I actually did vocals on a song or two. I don’t remember how many shows Purely Physical did, if any, except for one, in the driveway of my parents’ house. At that performance I did vocals on a cover version of Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”. I believe that this was in 1980 or so.

Aside from these experiences and an open microphone poetry reading in 1979, I had not had any musical performance experiences. I was not actively recording my own music prior to meeting Jaffe and I was unaware of the mail art movement.

As a teenager I had recorded a lot of television programs (such as “The Mary Tyler Moore Show”) on a cassette recorder and transcribed the screenplays.

Who were some of your early music and art influences?

In my early childhood I really did not take an active interest in music. I was occupied with reading lots of history books and was totally uncool. I remember singing hymns in church with my parents and that it was dreadfully boring and that nobody in my family could carry a tune!

It was not until junior high school that I developed an interest in rock music. I remember that one day in 1971 in a Music class in junior high all of the kids were supposed to bring a favorite record which we would all play for the other kids. I brought a schmaltzy instrumental 7-inch record by Paul Mauriat called “L’amour est bleu”, and the other kids remarking how uncool my musical choice was. I remember that one kid brought Paul McCartney’s 1970 album McCartney, and me thinking how weird and alien it sounded. In other classes kids were bringing in and showing off Pink Floyd (Atom Heart Mother) and Black Sabbath (Black Sabbath, 1970) records. I remember boring conservative Harold McGee trying in vain to date a hip Black Sabbath chick with tattered bell-bottom jeans.

The first rock concert I ever attended was The Osmonds, in 1971.

I redeemed myself on the second one by seeing Alice Cooper on their Billion Dollar Babies tour in Spring 1972, with Flo and Eddie (ex-Turtles) warming up. In my junior high and high school years and on into the mid-1970s I attended dozens of concerts and saw Kansas, Poco (four times), The Edgar Winter Group (notable for their use of an ARP synthesizer), Loggins & Messina, Dan Fogelberg (three times), Emerson Lake and Palmer, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Gary Wright, The Kinks, Chicago, Peter Frampton, Rod Stewart & Faces, Boston, Styx, Eagles, Yes, Kiss.

Also around 1972 I developed an interest in Chicago. People laugh at Chicago now as being Adult Contemporary Easy Listening style, but their first three or four albums were actually kind of edgy in a way, and aggressive and noisy in places. I remember that Terry Kath’s “Free Form Guitar”, on the first Chicago album, Chicago Transit Authority (1969), was actually a noise improvisation of sorts, and blew my mind.

Another formative album that I listened to endlessly was Pictures At An Exhibition by Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

Like so many kids back then I avidly collected rock record albums in my teen years, and had something like 700 records at the peak of my collection. I listened to a lot of The Beatles (especially their later albums), tons of David Bowie, Elton John, Jethro Tull, Bruce Springsteen, The Who (Live At Leeds was the album I listened to most – lots of feedback!), early Genesis (their 1973 Live album was freaky), and Fleetwood Mac (Fleetwood Mac and Rumours) in-depth. I never did like Led Zeppelin or The Rolling Stones (although I maybe should have!) all that much and still do not. It’s worth noting that at that time I considered “disco” to be a dirty word.

I had aspirations to make my own music, but I lacked any kind of natural ability, or the physical dexterity, to play a musical instrument, and I certainly did not possess the dedication necessary to practice. At one point I bought an old out of tune upright piano. I took piano lessons for several weeks, and did pretty well at it, but lost interest because of boredom from playing endless scales and finger exercises. A few years later I tried to take guitar lessons, but was miserable failure at it. I could not get my hands to do two different things at the same time.

I listened to plenty of guitar and drums bands in those days, but I often seemed to favor groups that had a keyboard player. I could relate to keyboard instruments, and thought that one day I would play them if any musical instruments at all. Looking back I guess it is because keys are a lot like buttons. It seems to natural to me that instruments should have keys, buttons, knobs, and sliders. Turn a knob or push a button to make a sound!

In my senior year of high school I took a Music Theory class and got an A in the class even though I could not play a musical instrument.

Throughout much of these years I hung around with musician friends and talked about starting bands with them, but nothing much ever came of it because I could not play an instrument.

Much of my early stage experience came from my heavy involvement in theater productions in junior high and high school. I always played the “character parts” – clown, rapist (in David and Lisa), redneck grandpa-type (Uncle Smelicue in Dark of the Moon), and others. I had a loud voice that carried well, and I could easily project my voice to the back of the auditorium seats.

Sometime in the mid-1970s I bought Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, listened to it once and then eventually sold it to a second-hand record shop.

In the Summer of 1976, after my Senior Year in high school, I was introduced to cannabis and after that my tastes in music changed.

When I got to college at Indiana University I found out about 1960s psychedelic music (10 years after the fact! – Jefferson Airplane, The Doors, etc.), Neil Young, and Bob Dylan. Neil Young and Bob Dylan were very important in the shaping of my musical voice as both of these artists relied to a great extent on simplicity of audio materials, and relied on timbre, delivery, and setting, with a lesser emphasis on technical virtuosity than the big flashy stadium rock bands whose fingers were flying a million miles per second. Dylan especially, with his mid-60s albums such as Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde On Blonde, had a huge impact on me. The album of his that had the biggest impact on me, though, was not these classics, but a live album from 1976, Hard Rain, which was an absolute revelation not only because of its vitriol and bile and bite, but because it was so brilliantly incompetent, and always on the raging edge of collapsing into failure.

This feeling of collapse and teetering on the brink of disaster is also what attracted me to much (if not all) of Neil Young’s records from the 1960s and 70s. Tonight’s The Night (1975) especially made a big impression on me! And later, Rust Never Sleeps. I saw Young in concert in Chicago at The Blackhawks ice hockey arena after Rust was released, and it was the loudest concert I ever attended, with joints being passed up and down the rows for the entire two hours.

Another entry in Hal’s ragtag falling apart album list is A Nod Is As Good As A Wink… To A Blind Horse (1971) by Faces. I listened to that album until I wore it out.

It was through my interest in Bob Dylan that I found out about Jack Kerouac and The Beat Generation. I read all of Kerouac’s books, and in 1979 I even moved to San Francisco for three weeks, thinking that I was going to give up the normal life and live the life that Jack described in his books.

And of course through my intense study of Kerouac I encountered the writings of William S. Burroughs, and after that my thinking about literature, reality, and music was never the same.

Much of the background and foundation for my work as an audio artist comes as much from avant garde literature as it does from musical influences. In my college years and on into my thirties I read about three books a week, and was well-versed in Camus (but not Sartre), Thoreau, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Carlos Castaneda, P.D. Ouspensky, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky (another foundation of my art).

Naturally, I experimented with LSD (taking it 13 times, which was enough!), and these experiences introduced to me new possibilities for multi-leveled thinking, reconciling supposed opposites, alternative realities, a sympathy for or understanding of synesthesia, the feeling of sound/music as tangible objects, etc.

Later, around 1980, when I was hanging around with Charly Krohe and those Herron Art School kids I found out about Talking Heads (More Songs About Buildings And Food, notably). Then from there I found out about Brian Eno! So it was at about that point that I started to investigate music-making that didn’t rely on technical skill, but relied more on texture, method/process, and atmosphere.

I found out about punk rock after it had already peaked, and I found out at this time about Sex Pistols, Devo, Patti Smith, Suicide, etc.

If I had to pick just two influences or inspirational foundational figures in my development as a noisician/audio artist I would have to choose Brian Eno and William S. Burroughs.

Prior to meeting Debbie Jaffe in August 1981, and then Rick Karcasheff, I knew nothing about:

Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, and the other Industrial bands; Joy Division, Durutti Column, Section 25, and bands associated with the Factory Records sound; nor did I know anything about Nurse With Wound and the United Dairies label; space rock and krautrock were unknown to me. I was yet to discover Dada and Surrealism.

My true formative education began in the Autumn of 1981.

What excited you about the home recording movement?

Rick Karcasheff introduced Jaffe and I to a lot of new sounds, the likes of which I had never heard before. He had amassed a collection of thousands of records and tapes of avant garde and experimental music, and when we visited him at his house he played selections from recordings he thought we needed to hear. He made tapes for us of things that we were interested in hearing more of: the bands I mentioned, above plus Soft Machine and other bands from the Canterbury Scene, The Residents (another band highly important to my development!), Virgin Prunes, Einstürzende Neubauten, Raincoats, The Slits, Wire and its offshoots, Magma, Univers Zero, Roedelius, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, etc.

Karcasheff also introduced us in 1982 and 1983 to numerous small press music and mail art zines, such as Factsheet Five and ND, in which we read about recording artists who were creating, producing, and releasing their own music on cassettes. As mind-blowing as it had been to hear and absorb in-depth all of the great classics of avant and experimental music I have detailed above, the real life-changing revelation was finding out about all of the great music being produced in the homemade music scene!

We wrote to many of the people whose tapes we read about in the reviews and listings in those zines, and traded tapes of our own music [such as 60 Minutes Of Laughter (1982), Viscera: In A Foreign Film (1983), and Viscera: A Whole Universe Of Horror Movies (1984)] with these other DIY music pioneers. These were people who were adventurously exploring sound without limits, without being concerned about money, or success, or making it. Contemptuous of the mind-numbing vacuousness of the mainstream music industry these homemade experimental audio recording artists blazed paths of their own choosing, often in a highly personal manner, their sounds mirroring or reflecting their personal experiences. When you received a cassette in the mail from a trading partner you knew that this was a special object, one of few in number, sometimes with elaborate or even very simple homemade/handmade artwork to accompany it.

As has been detailed elsewhere, by me and others, cassettes were items of devotion. Most notable is that they were accessible to anybody. Almost everyone could afford to buy blank cassettes, cheap recording gear, and tape machines for dubbing copies of your releases. Very few people in those days could afford to get their own vinyl records pressed. You could buy cassettes at a local store and make as many or as few copies of your release as you needed to. Also, quite importantly, you could actually interact with a cassette as a medium. Many cassette purists in those days used cassettes in every step in the creation process: from basic recordings to master tape to duplicated copies of the final tape release. This kept the means of artistic production completely in the hands of the artist his or her self — and this was revolutionary! Cliché or not, the (cassette) medium was, for me and lots of other people, clearly the message.

A point I want to emphasize very strongly, as I have at many times in the past, is that, while many people did use cassette releases as a stepping stone to getting labels to release their music on vinyl (or to future self-released vinyl), for many of us the cassette became an audio art form in and of itself – NOT merely a poor cousin of so-called “legitimate” releases on vinyl. These homemade cassette releases of experimental music also were not “demos”. “Demo” was and still is a dirty word to me.

Another point I want to stress here is that these were not “mix tapes”, for Godzilla’s sake! I have heard young people who were not around at that time mistakenly refer to these 1980s cassetteworks as “mix tapes”. What I am talking about were fully-conceived audio art/noise/music works, albums, complete works – not collections of or mixes of music by other people.

In 1984 the cassette was not an ironic hipster retro-chic fetish accessory in cute designer colors, or a design on refrigerator magnets, handbags and blinking website widgets.

The cassette was all we had, and for many of us all we needed, and wanted — it was everything, and we were serious about it. In spite of ever-present tape hiss and modest or primitive recording gear, we all strived to make tape releases that sounded as good as possible. Many of us in those days only dubbed our cassettes onto High Bias cassette tapes for optimal sound quality. if someone sent me a cassette on Normal Bias tape in those days I considered it an insult of sorts or I just figured that they did not really take their cassette release seriously. I do not remember anyone talking about “lo-fi” as an aesthetic.

Several hundred individuals, spread out over Planet Earth created their own unique, creepy, cold, haunting, bizarre, isolationist, existentialist, violent, harsh, “industrial”, assaultive, subversive, psychotic, psychedelic freakouts, spacy, electronic and mechanistic, screaming rants, fucked-up, nerdy, bacchanalic, Magick-ritual and Crowleyian-themed, bondage-and-S&M-themed, even racist and misogynistic, tribal-primitive, technological dystopian, weird, insane music in their bedrooms and living rooms, on their own terms. Today, when “outsider” and DIY music and Noise shows are commonplace, it is difficult to comprehend what this all felt like 25+ years ago.

Why did you and Debbie start the Cause And Effect label? What year would that have been? I’m assuming you started this imprint to house your own projects but did you ever have intentions to promote or distribute other artists, and did you?

In early 1985 Debbie Jaffe and I officially launched the Cause And Effect International Cassette Distribution Service. We distributed cassettes of homemade, independent and underground experimental, electronic and industrial music by artists in USA, Belgium, France, England, Canada, Germany, Holland, Spain, Italy, Northern Ireland, Switzerland, and Japan.

The January 1985 Cause And Effect Catalog contained listings for these cassettes:

Anatomy Of Coicidence compilation

OSLWMMGIB?: self-titled

Dega-Ray: Clasp/Click

Robert Rich: Sunyata, Trances, and Drones

Architects Office: Memorial Issue, Flowmotion, Dispensation

Pascal Comelade: Milano Enarmonisto

New 7th Music: New Humanity Switchboard, Modella

Paul Kelday: Worlds Apart

Yard Trauma: Reptile House

Mans Hate: Suffer In Silence

Objekt #2 compilation

Psyclones and Schlafengarten: Life Is Like Death With The Lights On

Psyclones: AKA-DPL

Maybe Mental: Animisum II

Schlafengarten: Torque, Memorandum

Cadavres Exquis compilation

S/M Operations: Live At The Harrington Ballroom compilation

Fetus In Fetu: self-titled

Viscera: Who Is This One, A Whole Universe Of Horror Movies, In A Foreign Film

Sadistic Gossip and Mary Davis Kills: Confessions Of A Shit Addict

Blackhouse: Pro-Life

Gertie: Overdoses Of Roses

Taste Of Tongues compilation

Sleep Chamber: Music For Mannequins

Band-It #16 cassettezine

Déficit Des Années Antérieures: La Famille Des Saltimbanques, Prehistoric Rejet

Gerechtigkeits Liga: Live In Antwerpen

Swamp Patrol 84

Cleaners From Venus: Under Wartime Conditions

Twa Digs Under Paris: I Shin Ohn

Avant-dernières pensées: Arte Deschecho

Artless Time: Shells From The Italian (A)isle, and Inarticulate Volition

The Phallacy: self-titled

Sensationnel 2 Le Journal compilation

Kevin Harrison – Steven Parker: Against The Light

Un Departement: self-titledT

FaLX cerebRi: Rite 64

Gut Level One: A Compilation

Psychological Warefare Branch: self-titled

The Last Supper compilation

SMERSH: Make Way For The Rumbler

Walls Of Genius: Before …And After, and Crazed To The Core

Jack: Up

Noisy But Chic compilation

Bloody But Chic compilation

Bene Gesserit: Live In Belgium And Holland

4 IN 1 compilation

Insane Music For Insane People Vol. 1, 2, and 3 compilations

Magthea: The Chilliness Of These Sounds Is My Cell, Nothing Left To Believe In, Magthea And Insanity

Magthea And Soft Joke: A Soft Magisch Joke Theaterproduction

Magthea And Mr. Minimum: self-titled

Audio Communication Compilations #3 and #6

Theatre Of Ice: Beyond The Graves Of Passion, The Haunting

Occupant: No Specific Answer

Marco Cacciamani: Step

HTHeW: Galaxy

Pliny The Elder: Torpid Liver / Tim Zukowski: Observations, split tape

Audiologie compilation

Vox Populi!: Introduction À La Théorie De La Subjectivité Relative

Ritual Dos Sadicos compilation

Onslaught #3, #4, and #5 cassettezines

L.A. Mantra I & II compilations

Randall Kennedy: Scenes Of Redemption

Mystery Hearsay: self-titled

60 Minutes Of Laughter

John Wiggins: Anagenic

X Ray Pop: After Bathing At Berlin With Adolf

Dog As Master: Coffee Spleen & The Barking Dog

Tara Cross: Concocting Chaos

Benjamin Allen: Film Soundtracks

Vito Ricci: Postones

Jarboe: Jar

Gargoyle Mechanique: House Of Dogs

Malcolm: Macac

The Room 101 O.P.D.: September 1984

Bande Berne Crematoire: self-titled

Nisus Anal Furgler: self-titled

Drunken Dolphins: self-titled

Aural Fixation compilation

If, Bwana: Freudian Slip

Big City Orchestra: Number Five

F/i Zombie

Richard Franecki: Points, Two Drones

P16.D4 Wer Nicht Arbeiten Will Soll Such Auch Nicht Essen!

Test Department: Live At The Ritz New York July 1984

Der Akteur: The Accident In The Year Dada X

Polar Praxis: Werk Eén

Ptose: Poisson Soluble

O’Nancy In French: self-titled

Roberta Eklund: Piano Improvisations

Mr. Herz: Herziaanse Golven

Hashimoto: Makuraga

Takahashi-Numazawa-Hashimoto: Koutei

Master/Slave Relationship: The Desire To Castrate Father

Jaffe and I started the Cause And Effect Distribution Service because we felt that cassette releases were not being given adequate distribution that they deserved. Most distributors at that time still preferred to distribute vinyl records. Cassettes were very much considered second-class citizens and were not taken seriously as legitimate releases by many if not most people. Ironically, this was because anybody could do it! Because anybody and everybody had the means to produce a cassette release, this meant that record labels did not choose who was deserving; individuals chose for themselves. This was not only a subversion of the mainstream music industry, but even the so-called independent music scene at the time. The cassette was a defiant big middle finger. We modeled Cause And Effect on Kent Hotchkiss’s Aeon Distribution Service of Fort Collins, Colorado. We were the only distributor that I know of at that time that carried only cassettes, no records.

It is worth noting here that these Cause And Effect photocopy-print catalogs (designed by Jaffe, with texts by me) contained pictures of each tape cover, along with a paragraph-length description of each release.

A few months later, with our second catalog, things had changed a little. The May 1985 Cause And Effect Distribution Service Catalog contained listings for 109 distributed cassette releases from other labels.

Additionally, there was a special section in the catalog for “Cause And Effect Exclusive releases”: cassettes by Borbetomagus, Pacific 231/Le Syndicat, Vox Populi!, Merzbow, Controlled Bleeding, etc.

The newly-created Cause And Effect label section of the catalog contained listings for cassettes by Viscera, Dog As Master, Master/Slave Relationship, Monochrome Bleu, Robert Rich, and more; plus reissues on the CAE label of the entire Uddersounds label (F/i, Richard Franecki, etc.) catalog up to that time.

Plus we distributed several zines and other publications such as OP, Unsound, No Commercial Potential, The Other Sound, Artitude, CLEM, etc.

So, while we had continued distributing cassettes that were produced by labels all over the world, we had also started what we called “license distribution”, which was that the labels would send us a master tape, printed covers or an artwork master, and we would make copies as we received orders for them and then pay the labels.

Looking at the Summer 1986 Cause And Effect Catalog I see that by that time we had completely abandoned distributing titles by other labels, and had concentrated on Cause And Effect label releases, including of course our own cassette albums by Viscera, Dog As Master, and Master/Slave Relationship, as well as a 3-cassette box set of the first three Nurse With Wound albums, and exclusive releases by many other then well-known names in the experimental music underground.

I will say now in retrospect that I regret this course of action.

Is there an online version of any early Cause And effect catalogs?

No, there is not. Some day I hope to put scans of the pages from these catalogs online. They would be interesting and I think valuable documents of those days. This is one of many hundreds of things I need to put on my “to-do list”.

You and Debbie also collaborated as Viscera. How did the music generally happen? Would one of you bring an idea or was it more improvised?

In my description of the making of the 60 Minutes Of Laughter cassette I have written:

“60 Minutes Of Laughter contains the earliest recordings by Viscera, from the Summer of 1982. That Summer Deb and I started developing some pieces in which I would recite, sing or act out poems and stories we’d both written, and Deb would compose a minimalist background/ backdrop or mood setting using simple instrumentation – mostly our Casio VL-Tone mini keyboard.”

You can read more about 60MOL here

And about the Viscera recordings on In A Foreign Film I have written:

“The equipment Debbie Jaffe and I used was primitive, but was a step up from 60 Minutes Of Laughter. Along with the tiny toy-like Casio VL-Tone, we had a new Casio MT-11 polyphonic keyboard. We had recently bought a Boss Dr. Rhythm DR-55 drum machine, just like the one our friends Rick Karcasheff and David Mattingly used in their band Gabble Ratchet. Deb played clarinet on a couple tracks. We performed most of the vocals using our Shure vocal microphone through my guitar amplifier. We used the amp for the keyboards too. All of the pieces on In A Foreign Film were recorded with an Audio Technica stereo microphone directly into our Pioneer CT-F750 cassette deck, which had stereo mike inputs on the front.”

and

“Deb and I set about making our own unique and very personal audio statements. One of us would choose a poem or other scrap of writing by one or the other of us that we found lying about or in a notebook; the other would search for a sound setting on one of the Casio keyboards or a simple pattern on the drum machine. Then, with little or no preparation or advance planning we would turn on the tape recorder and let it flow out of us! We filled up several cassettes with these spontaneously created sound works. In a way they were like miniature audio theatrical pieces.”

I answer this question in greater detail here

in my history of the In A Foreign Film cassette by Viscera:

You also had your own Dog As Master project going then too. It seemed more confrontational or maybe I am just misreading the intent. Did you have an idea for a particular sound for either of these groups?

Dog As Master was my solo project which I started in 1984 and it allowed me to explore music of a more abstract, noise- or sound-as-sound based nature than generally had been explored up to that point in the Viscera duo. Dog As Master was possible because in the Spring of 1984 Jaffe and I had purchased our first four-track cassette recorder, a Fostex X-15. This gave us both the freedom to be able to investigate individual, personal ideas. This also to a great extent spelled doom for Viscera, because after that, Viscera tapes were mostly collections of songs by each of us, with the other person adding bits and pieces of sounds here and there. Many of the Dog As Master recordings do indeed contain harsh, abrasive textures of electronic, heavily-manipulated musique concrete multi-tracked tape collage industrialism. But all with an underlying sense of humor!

When did you first come into contact with Al Margolis (Sound Of Pig label)? And when was your first collab with Al?

I believe that I first came into contact with Al Margolis through a review of a Sombrero Galaxy cassette in Daniel Plunkett’s ND zine. I wrote to him and we traded tapes, in maybe 1984 I think. Al and I first collaborated on Side B of the An Organized Accident cassette on his Sound Of Pig Music label. Side A featured the first recordings by Dog As Master.

I fondly remember the “Untranslatable” cassette which was an electronic, droney outing that verged on minimal and even ambient. At the time, this seemed a departure from what I knew of your music. Did you each exchange backing tracks?

Untranslatable was an outstanding work if I do say so myself, and one of my favorites in my catalog. There is a lot of space in the sound of the tape. Al sent to me two cassettes on which he had recorded material on Tracks 1 and 2 in his four-track cassette recorder. I added sounds on Tracks 3 and 4, recording on my Fostex X-15. Al left a lot of blank tape between the separate pieces so that I would have a clear idea of when and where one piece ended and another began. When I mastered the tape I left those lengthy silences between the pieces!

What about Chris Phinney (Harsh Reality Music), when did you first meet him through the mail? And when was your first musical collaboration? Did you also meet him in person then?

Chris contacted me pretty early on, around 1984 I think, and sent me his Malice fanzine. During our discussions about those times Phinney has recounted that I never wrote him back, or did write and told him I was not interested. I don’t remember which!

We met on October 30, 1987 when Al Margolis and I visited Memphis while on tour. We played at the Antenna Club, in a show arranged and promoted by Phinney. Chris later released my solo set that night on the Dog As Master Live In Memphis cassette on his Harsh Reality Music label. Soon after that we started trading tapes on a regular basis. It was not until after I had moved to Florida in 1988 that we started collaborating, through the mail and in person in Apollo Beach. Chris came to Apollo Beach in October 1989, and at that session we recorded our first collaboration tape, Usufruct. Next was a mail collab called Heads. He returned in March 1990 for another session, at which we recorded Maneuvers and Shell. Chris and I had an instinctive connection on a highly intuitive level, and most of these in-person recordings were straight-up improvisations, and highly abstract electronic music, forged with analog synthesizers, such as the Moog Rogue, ARP Axxe, Moog Prodigy, Korg MS20 and the Korg Poly 800. In June 1990 I returned to Memphis and at that time we recorded the Skull cassette and Ditch with Michael Thomas Jackson.

I believe you did live performances as Dog As Master. Did you ever travel out of your local area to do these? And how was it received?

I did an impromptu performance with JABON (Scott Colburn) on September 24, 1986, and I released this on Cause And Effect as the Incidental Vibrations cassette.

On May 16, 1987, JABON and I traveled to Pittsburgh and each performed solo sets and a duo set at a show put on at Carnegie-Mellon University by Manny Theiner of the SSS label. My Dog As Master performance was released as Dog As Master: Live In Pittsburgh, and the duo recording with JABON was issued as Incidental Vibrations 2, both released originally by Cause And Effect.

In October of 1987 Al Margolis and I embarked on our If, Bwana and Dog As Master (Bwana Dog) Sacrifice Of Reason Tour. We performed together at Bar None in Brooklyn, on Dave Prescott’s radio show on WZBC in Boston, at The Rivoli in Toronto (in a show organized by Myke Dyer of John Doe Recordings, with show opening act Violence And The Sacred), at a sports bar in Windsor, Ontario, and at The Antenna Club in Memphis. We played to a large audience in Toronto and actually made $500 that night! In Windsor we played to about five or six people. In Memphis there was a highly-enthusiastic audience, and several notable bands playing at the show including Mystery Hearsay and Viktimized Karcass. Selections from our tour recordings were later released on Bwana Dog: Painting and Bwana Dog: Live In Toronto.

In case you are interested ,Viscera performed live twice: the first was in like 1984 or 1985 in either Anderson or Muncie, Indiana, I can’t remember which and was a miserable experience. The second was on August 28, 1986 at Phyllis’s Musical Inn in Chicago, in a show headlined by Algebra Suicide. The live recording from this show was released as Viscera: Snot, by Cause And Effect, but really was not very good I don’t think, as we did cover versions of our own material.

Your history takes a lot of twists and turns over the years. I sort of remember you disappearing for awhile and then re-appearing fresh and energized with a new direction. Was this actually the case? Would you burn out and then rise like the phoenix?

Yes, I dropped out for a bit after I moved to Apollo Beach, Florida in 1988, but it did not take long before I resumed heavy music recording and networking activities, with the Electronic Cottage magazine, and extensive collaborations with Chris Phinney.

I actually stopped all music activities altogether from 1992 to 1995. This resulted from total burnout from publishing Electronic Cottage, and began shortly after I moved to Gainesville.

Oh, and there was brief burnout for about one year in 1999, after finished the Tape Heads compilation series. I did not stop making music during this time. Brian Noring and I recorded a lot of music together that year, and that was the year that I did all of the paintings that you can see in videos and photos of my apartment.

Ever since then my activity level has been fairly consistent, and I would say that I am just as productive now as I ever was, even as much as my peak productivity year of 1986.

Let’s talk about Electronic Cottage. This was your self published magazine about the underground scene. What gave you the idea to do this? It must have been a tremendous amount of work. What kind of satisfaction did you get from it? Or frustration?

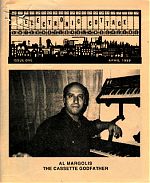

Electronic Cottage Magazine was “An inside look at the Home Taper Phenomenon, Cassette Culture and Electronic & Experimental Music”. I published six issues: the first in April 1989, the last in July 1991.

I moved in to my sister’s apartment in Apollo Beach, Florida in 1988, at the age of 30, and I felt like I was starting my life over completely. My relationship with Debbie Jaffe, with whom I had lived since Autumn 1981, had totally disintegrated; and I felt a deep sense of frustration that near its end Cause And Effect had totally lost sight of its original goals and purposes.

Apollo Beach is a sailboat bedroom community on a man-made peninsular thumb, sticking out into the east side of Tampa Bay, 20 minutes from downtown Tampa, and essentially “out in the sticks”, near a heavy agricultural area. I got a job as a cook at the Holiday Inn down on the beach, just down the street from where I lived. The mile and a half long Apollo Beach Boulevard was the one route in and out, and on either side streets branched off that were lined with apartments and houses that pretty much all looked the same, situated on canals in which mullet jumped. At its intersection with U.S. Highway 41 there was a Winn-Dixie grocery store, a post office, two or three other shops, and a handful of bars. I did not own an automobile, so I was completely dependent on friends and relatives to provide rides to points of civilization, the nearby large cities of Tampa and Saint Petersburg. Aside from my Miniature Dachshund, Kaffee (pronounced like “coffee”) and Golden Retriever, Cosmo, and the people I knew at work, I was totally isolated.

After a few months of these desolate conditions I got “the itch”, meaning that I missed getting mail from my friends, missed getting cool tapes of experimental music in the mail, missed being involved in the vibrant hometaper scene. I got tired of going to my mailbox every day and finding nothing in it, no packages containing cassettes! I decided that I needed to re-dedicate myself to the original principles of the do-it-yourself underground experimental music tape network, which I had so sadly lost sight of in the midst of the madness and the turmoil of my last year or two in Indianapolis. I wanted to serve and promote the scene in some way, in some relatively unselfish manner.

At the time I and several of my cassette friends felt that there was really no publication that was covering cassette music in any kind of consistent fashion. When OP magazine ended, and splintered into Option and Sound Choice, serious coverage of Cassette Culture, and reviews of cassettes, were spotty and inconsistent. It seemed like there was an emphasis in those publications on vinyl record releases, and more upscale indie labels (especially in Option). These magazines were a big disappointment to me and a lot of my friends.

So, I decided to publish a magazine that would report on and take Cassette Culture seriously. This is similar to the reasons why I started the Cause And Effect Distribution Service back in 1985 — because nobody else was doing it! —- because nobody else was taking cassettes seriously as an art form the way I thought they should!

In what must have been late 1988 I created a small paper photocopied leaflet announcing a new zine that would cover the cassette scene. I stuffed these into envelopes that I mailed to my friends and asked them to spread them through the network by putting them in packages of tapes that they were sending to their contacts. I must have sent out something like 5,000 of those leaflets.

I solicited the help of my friends and asked them to write articles, interviews, reviews, artwork and editorials for the first issue. Sue Ann Harkey designed the Electronic Cottage logo which would appear at the top of the front cover of each issue.

The first four issues were published in the format of 8.5 inch by 14 inch folded, stapled sheets, making 8.5 inch tall by 7 inch wide pages. All six issues were offset printed at Action Printing in Tampa. I did 1,000 copies each of the first four, and 700 copies of the last two, which were printed on 8.5 by 17 inch sheets.

I typed up the texts on my dad’s Macintosh computer at his architectural office in Tampa. I remember that I had to use 3.5 inch floppy disks to save anything on that computer, and I had to keep shuttling disks in and out of it. I printed out the texts, brought them home, and hand-pasted them together with the ads and artwork onto 8.5 by 14 inch sheets.

I got the printed uncollated sheets back from the printer in big boxes. My mom helped me collate, fold and staple the 1,700 sheets that made up the 1,000 copies of the first issue. I did the construction of the zines themselves to save money. That was a lot of work!

The 64-page Issue One of Electronic Cottage featured Al Margolis, “The Cassette Godfather”, on the cover, and inside were editorials, articles and label and zine (ND for example) overviews by myself, Dave Prescott, Carl Howard, Miekal And, Amy Denio, Jeph Jerman, Al Margolis, and Scott Colburn; and in-depth interview with Margolis by PBK; and 41 reviews of cassettes and records, plus reviews of publications.

The reviews in Issue One were written by me, Andrew Orford, Al Margolis, Chris Phinney, Dave Prescott, Bill Waid, Dan Fioretti, Carl Howard, John Hudak, Allan Conroy, John Collegio, Jeph Jerman, Roger Moneymaker, Robin James, and Bret Hart. I urged all of the reviewers to write careful, thoughtful reviews that took into account and placed the reviewed release in the context of previous work of the artist. Each review contained the postal address of the artist or label, so that readers could acquire the tapes directly from the source. Scanning the reviews I see releases by Geoff Alexander, Algebra Suicide, Dennis Andrew, Prescott and If Bwana, Don Campau, City Of Worms, Darren Copeland, Amy Denio, The Dental Conference, Minoy. Sue Ann Harkey, IAO Core, Illusion Of Safety, La Sonorite Jaune, Le Momo, Mental Anguish, Nick, Odal, PBK, Suckdog, Terre Blanche, This Window, many compilations, and more. I reviewed 10 publications including Bananafish, Xerolage 14 by Malok, Photostatic, Afterbirth, etc.

There were tons of cool-looking classic advertisements in that first issue: Jeph Jerman’s Big Body Parts label, Phinney’s Harsh Reality Music label, Vidna Obmana, Sound Of Pig, Ecto Tapes, Mike Jackson’s XKurzhen Sound label, Myke Dyer’s John Doe Recodings label, Generations Unlimited, Gravelvoice Records, Projekt, Intrinsic Action, ND zine, Lord Litter’s Kentucky Fried Royalty, an Alamut Records/BBP ad for a Haters release, Jeff Chenault’s International Terrorist Network, Artware, Radical Cunts Anonymous Records, Carl Howard’s audiofile Tapes label, and many, many more.

I recently scanned all of Electronic Cottage Issue One and uploaded it to the Internet Archive. You can view and download the pages here

The 68-page Issue Two of Electronic Cottage (September 1989) featured Chris Phinney (“Master Of Harsh Reality”) on the cover; an interview with Phinney by Roger Moneymaker; an article on Pat Andrade by Myke Dyer; an article called “Home Music Projects For Kids” by Walter Alter; “Procedures For Success In Home Recording” by Zan Hoffman; plus editorials.

Electronic Cottage #2 had lots of reviews of cassettes and records, including 1348, Alien Planetscapes, Arcane Device, Blowhole/Big Joey, Bwana, City Of Worms, Dave Clark & Walter Drake, Richard Franecki, The Haters, Zan, Eric Lunde, Morphogenesis, NOMUZIC, Odal, Prescott, PBK, Rik Rue, The Silly Pillows, Sponge, Teen Lesbians & Animals, Warworld, Gregory Whitehead, Zzaj, and more. Plus reviews of zines such as Cargo Cult, Factsheet Five, File 13, Gajoob, H23, Metro Riquet, Photostatic, and Vital. plus lots more cool advertisements by ROIR, Dennis Andrew, Suckdog, PBK, AWB Recording, Ecto Tapes, Gen Ken Montgomery’s Generator, aT, Hybryds, J. Niswander’s Usward label, Turn Of The Grindstone, Michael Horwood, Intrinsic Action, Harsh Reality, more.

EC#2 also included letters from readers, with their reactions to the first issue.

In my editorial introduction to Issue Three of Electronic Cottage (March 1990, 68 pages, Dave Prescott on the cover) I wrote:

“ELECTRONIC COTTAGE is a publication dedicated to contemporary independently-produced electronic folk arts and culture. It’s all about audio pioneers, sonic explorers, contemporary electronic music trailblazers and the independent do-it-yourself spirit. It’s all about people who aren’t just content to sit back and consume what the mass media serves up on a remote control platter, but are producing new, exciting, challenging and highly personal artistic visions in their homes, much like the folk artists of the past. The mass media is running scared because it no longer has a monopoly on information and communications systems. More than ever before the individual has the power and freedom to create and communicate in his/her own way and share that vision with other people in every corner of the Earth. We stand at the threshold of an exciting new age. Art is now more democratic than ever before – Art for all, not just for an elite few! The tools are there photocopiers, cassette recorders, personal computers waiting for you to utilize them. While the millions of the couch potatoes in the world rot, thousands of adventurous spirits in every corner of the globe are forging an exciting new scene, reaching out to listeners, sharing, synthesizing and cross-pollinating ideas, cultures and visions.”

Electronic Cottage was certainly not without its controversies!

In the editorial statement above I referred to the hometaper movement as “independently-produced electronic folk arts and culture”. My use of the term “folk” and my notion that homemade music was a new folk music drew heavy criticism.

It is worth noting that recently on Facebook I got a detailed, lengthy discussion going on this topic, and that there was not nearly the opposition to the idea now as there was 20 years ago. What I meant then as now is that we have used everyday consumer level technology to create our own music, and much of that music reflects our experiences. It has always been my understanding that the cassette was originally developed and intended as a utilitarian dictation device by its developers. I think that it was only later that the sound quality was improved so that the portable cassette recorder could replace the bulky reel to reel deck. Even then, at best I think that the cassette was only intended to provide snapshot-quality copies. In this case it was intended as an aid to music consumers, so that they could make personal copies of their vinyl record albums, which were difficult to transport and play. Lo and behold, some smart people in the late 1970s got the idea to make copies of their music onto cassettes and treat them as audio art objects. A later example would of course be circuit-bending, and it is obvious that this amounts to a re-appropriation of discarded junk technology. There are plenty of ironies here for me: one of which is that multinational corporations have enabled the anarcho-democracy and DIY individualism that we are discussing.

As Don Campau once said, “folk music is whatever the folks are playing”. The homemade experimental music and noise movement is in every sense a grassroots bottom-up participatory egalitarian anarcho-democratic phenomenon.

In the letters to the editor section (“Feedback”) of the second issue I drew criticism for publishing a review by Jeph Jerman of Terre Blanche’s “The Sickle Cell” 7-inch record. Lydia Tomkiw wrote:

“ …the Terre Blanche review offended us greatly. It supports, advertises, and sympathizes with the white power movement and attitude despite its lame disclaimer that the reviewer doesn’t agree with Terre Blanche’s racial standpoint. Terre Blanche’s political view is part of their music, because they want it to be: they have declared it, and they have integrated it into their music, and their intent is clear, focused and deliberate. One cannot separate their political viewpoint from their music because of this… We are surprised that a magazine as fine as EC would print such a review…”.

On the inside front cover of EC #2 there was a full-page ad for AWB Recordings, which released “The Sickle Cell” (along with two other releases, by Sigillum S and Intrinsic Action). And again, there was a full-page advertisement by AWB on the inside front cover of EC #3! And again on the inside front cover of EC #5!

My decision to print a review of an underground music artist whose themes were clearly racist, and my insistence on accepting advertising dollars from this same racist organization drew understandable outrage and condemnation by many members of the underground. Many folks who had supported the earlier issues eventually withdrew their advertising support, and there was widespread grumbling about EC. I explained that my position was that Electronic Cottage reported on and represented the hometaper movement as a whole, without censorship, warts and all, just the way it was, pretty or ugly. Doug Walker, of Alien Planetscapes, who had himself been a member of the Black Panthers, reluctantly agreed, with strong reservations of course, that my decision was the correct one.

Would I make the same decisions if I had them to make over again? I made what I thought was the correct decision at that time, based on careful, deeply-thought-out consideration. The decisions I made in this regard were indeed highly questionable, and worthy of criticism. But criticism is not a bad thing. Nor is controversy. I have always hoped that I am brave enough to do what I think is the right thing to do, right or wrong, regardless of how troublesome, regardless of the personal cost. Today the reaction to my decisions back then might be even worse.

Electronic Cottage was a public service project. It was there to inform, to educate, to share ideas, as a forum. I made no money from it personally, and I put hundreds of hours of work into it. I did what I thought was best for the community as a whole, even if that was “difficult”, contentious, controversial, painful. I was a firm believer that the open exchange of ideas and viewpoints in the hometaper community would enhance its growth. There was heated debate and discussion and fiery disagreement in those pages. The editorials by various writers, on a multitude of topics, got people fired-up! At least they talked about it, aired their thoughts and anger and disappointments and differences of opinions. How is this a bad thing, even today?

To fund the magazine I sold advertisements. Example, for the second issue full-page ads were $40, $25 for a half page, $15 for a quarter page; and classified ads were $2 for the first 25 words, $0.10 for each additional word. I also sold subscriptions: three issues for $7.00 in the USA, or $3 per issue. The first four issues of Electronic Cottage totally paid for themselves, and I made enough money off of the first four to pay for the next issue.

More controversy in Electronic Cottage #3! After the first two issues I decided to not publish reviews of releases any more, because I felt that reviews served as mere consumer guides, and didn’t serve the seriousness of Cassette Culture and homemade music. This totally threw a lot of people for a loop. It was incomprehensible to a lot of folks that a zine covering underground music would not contain reviews of recordings! This caused more fallout of a sort.

What EC #3 did have was a wealth of in-depth articles, interviews, and editorials which went into detail about the themes and ideas behind the making of underground music. I felt that this served to treat the scene with the seriousness it deserved. EC #3 contained lengthy interviews with Prescott, Dan Burke of Illusion Of Safety, Takehisa Kosugi, Randy Greif, and Rik Rue; plus artist and label profiles and essays on media criticism and the nature of noise and other topics — including Vidna Obmana, XKurzhen Sound, an appreciation of Lawrence Salvatore by Dan Fioretti, the cultural aspects of improvisation by Rotcod Zzaj, and more and more. Lots of reading!

Electronic Cottage Issue Four (72 pages) was published in July 1990, once again, in an edition of 1,000, with La Sonorite Jaune on the cover. This was the second full issue to not contain reviews, and there was a wealth of articles: a label profile of Midas Music by Chris Phinney, John Wiggins interviewed by Michael Chocholak, a profile of the Irre Tapes label by Dan Fioretti, Crawling With Tarts interview by Bill Waid, “Chatting Up Little Fyodor” by Jeph Jerman, an interview with Jack Hurwitz and Treiops Treyfid of Poison Plant Music, John Gullak interviewed by dAS, and the main interview of La Sonorite Jaune by Eric Therer, plus an essay on tape trading by Dimthingshine, and an article on Jorg Thomasius by Dave Prescott after the Berlin Wall came down.

In EC #4 I placed an announcement for the upcoming Electronic Cottage International Compilation Series, which was planned to be 10 compilations. I actually ended up publishing three 90-minute compilations. Any and all styles were welcome.

In many ways the advertisements in the issues of Electronic Cottage say as much about those days as anything else!

With Electronic Cottage Issue Five I started publishing the zine in a larger format, of 11 inch by 17 inch sheets folded in half, folded and stapled, making 8.5 inch by 11 inch pages. EC #5 and #6 were published in editions of 700 each.

Electronic Cottage Issue Five (January 1991, 84 pages) has Don Campau on the cover in what I think is one of the classiest and coolest artist pics ever! I thought Don looked so cool in that photo, and I wished that I would be that cool! In this issue we have Ken Clinger interviewed by Fioretti, Lord Litter interviewing Rodolfo Protti of Old Europa Cafe label, John M. Bennett interviewed by Dimthingshine, my interviews with Carl Howard and with Doug Walker of Alien Planetscapes, Carl’s featured interview with Campau, Chris Phinney’s interview with Alternate Media, profile of V2 Organisation, an article by G.X. Jupitter-Larsen called “Celebrating Entropy; the conceptology of haterdom”, plus lots more. And again, lots of classic ads, including one on the inside front cover by the AWB label, which states, in big letters “AWB RECORDING ARTISTS ARE RACISTS”.

The sixth and final issue issue of Electronic Cottage was published in July 1991 in an edition of 700. On the cover was Torrance, California audio artist Minoy (interviewed in-depth in the issue by Minoy expert Jack Jordan). This was a great issue, containing: Lord Litter’s report on the hometaping scene in Latvia, Swinebolt 45 interview by Phinney, King Felix interviewed by Dimthingshine, a profile of Bret Hart by Rotcod Zzaj, L.G. Mair interviewed by Carl Howard, a conversation with Walter Wright and Michael Herndon by Boyd Nutting, Jim O’Rourke interviewed by Jeph Jerman, an article titled “As It’s Dripping Down My Leg, A Story About Banned Production”, and much much more.

How many issues did you do and what finally ended it for you?

After six issues, enough was enough. The personal toll was just too much. All of the correspondence; the collating, folding, stapling, laying out of the pages by hand, mailing packages; solicitation of advertising and subscriptions and keeping track on the money situation. Remember, this was essentially a one-person operation aside from all of the great contributing writers. I made a mistake going to the larger format of EC #5 and #6. It increased the production cost of the magazine, as well as making them heavier and therefore more expensive to mail out, and I started having to fund the magazine with my own money. It became harder for those who had advertised before to raise the money for the increased ad sizes (and prices). Those were the first two issues that did not pay for themselves through advertising and subscriptions. Plus there was the emotional toll that I experienced dealing with criticism of my policies.

I experienced total, complete absolute burnout on a personal level. Plus I had troublesome personal issues (most notably an affair with a married woman 10 years younger than me who worked as a waitress at the hotel where I worked) which precipitated my move to Gainesville from Apollo Beach. It is worth noting here that for the three years I lived in Apollo Beach I was a kind of hometaper hippie of sorts. I grew my hair to my waist, and smoked marijuana every day for those three years (as I had during my last three years in Indianapolis). All of the pot smoking just added to the fatigue and confusion of my situation with the zine.

I also want to say here that Chris Phinney and I recorded several cassettes of analog synthesizer music together during this three year period, during visits by Chris and his family to Florida, and one visit I made to Memphis. These were initially released on Phinney’s Harsh Reality Music label and my Electronic Cottage label. Phinney and I did trio albums with Dimthingshine and Mike Jackson. I also recorded Peat (which is one of the best and best-known works in my catalog) with Al Margolis in 1990 (during a trip to the New York City Area), and a during a trip to Miami I recorded a tape with Dimthingshine and artists down there. It is worth noting that on these releases I used my own name, not a pseudonym such as Dog As Master. The tapes with Phinney were billed as being by Phinney/McGee, and unlike our earlier collaborations, Peat was by Margolis/McGee, instead of by Bwana Dog, or by If, Bwana/Dog As Master. It is also worth noting that during the Cause And Effect era I did not release any solo material. Clearly my emphasis during this time was on collaborative community-based thinking.

Then there must have been some kind of break but fairly soon you kicked it up again with HALzine. Why did you do this rather than just re-start Electronic Cottage? How many issues of HALzine were there?

Actually, I completely dropped out of the underground music scene for about three years, from 1992 to mid-1995. I moved to Gainesville in October 1991. The situation there in Apollo beach had gotten too difficult on a personal level, and I had to get out of there pronto. I, my two cats, and my dog moved into a one bedroom apartment with my dad. I was unemployed for my first three months in Gainesville. In January 1992 I got a job in the Food and Nutrition Services Department of Shands Hospital, where I have worked since then. Also, I moved to a new apartment at 1909 Southwest 42nd Way, where I have lived since.

In 1992 I started an intensive involvement with organized religion and joined the Bahá’í Faith, which stresses the spiritual unity of all mankind and racial harmony. I need not go into any more detail here about those years, except to say that I devoted myself as fervently to that cause as I had previously to underground music and cassette culture.

I published the first issue of HALzine in February 1997. On the cover was a photo of Brian Noring (of F.D.R. Recordings) and his wife, Kathy, that was taken during their January 1997 visit to Gainesville.

The focus of HALzine was clearly different than Electronic Cottage and I clearly stated the differences in the first issue of HALzine. On the front cover it says “artistzine” and “a personal zine by the creator of Viscera, Dog As Master, Cause And Effect, Electronic Cottage and HalTapes”.

On the inside front cover are advertisements for my va10 cassette release, and Cry Of The Banshee, a collaborative cassette release I had done with L.G. Mair.

On the first page in small typed cut-outs pasted haphazardly over a collage of images of my face were clues as to what HALzine was all about:

In addition to notes about my love of coffee and spicy food, riding my bike to work every day, a brief note on where I worked, and the facts that “I do not own an automobile, a television, computer, microwave oven, telephone answering machine, cell phone or pager”, and that my living companions were a Beagle and three cats, I state that “HALzine is a personal zine. It’s meant for those who have similar interests, which is to say — hometaping!”. Also, significantly “The only thing that really matters to me is creating my own homemade electronic and experimental music audiocassette recordings and sharing them with my friends all over the world!”

So, the focus of HalZine was much more specific, on my personal experiences as a homemade music audio artist. I wanted to share and others of similar interests my experiences. I felt the need to share the ideas behind what I was doing on a personal level without the financial responsibilities and all of the work that came with a much larger, more universal publication like Electronic Cottage.

It is worth noting that I printed HALzine in the 7 inch by 8.5 inch page format of the first four issues of Electronic Cottage.

The bulk of HALzine #1 consisted of an in-depth 13-page label profile of Brian Noring’s F.D.R. Recordings label, based on interviews I did with him. I want to go on record here as saying that when I re-surfaced in the hometaper world in 1995, a lot had changed. Many of the people that I had associated with in the Cause And Effect and Electronic Cottage days had abandoned the cassette format, were releasing records or CDs, were trying to gain notoriety and “success” for themselves, had moved to “bigger and better things”. Plus, the term “Noise” was starting to come into common usage. Noring’s F.D.R. label was to my mind a shining example of a mid-1990s label that was keeping the cassette audio art form alive with the original no-nonsense true-to-DIY roots and doing it in a personal way philosophy which had energized the tape culture in its early days. To me F.D.R. was the quintessential cassette label of the second half of the 1990s.

Toward the back of HALzine I had a few listings of “Hometaper News”, just news bits of a few of my tape trading partners.

I want to share with you here a statement from HALzine #1 that pretty well sums where I was at with my hometaper activities, what was important to me:

“There are innumerable reasons why tape labels come to an end: the tough financial demands of running a label; the demands and stress of day to day living; disappointment and frustration and feeling that nobody cares. We have to do these hometaping activities first and foremost for the joy and love of doing it. Sure, you always want other people to like what you’ve done. But you have to do it for yourself, because it’s important to you to make music, sound paintings, noise, etc.

Secondly, it’s important to keep in mind that probably not a lot of people are going to like what you do. It’s your sound art. It’s your personal artistic statement, with no compromises, no restrictions. You can try anything. But it’s not usually a money thing. I don’t even think about “breaking even”, making a profit.

A third point: it’s important not to overdo it, not to get overambitious, not to spread yourself too thinly. Keep it simple. Set yourself simple goals. Achieve those simple goals consistently. For instance in 1996 I set myself a goal to send out 600 HalTapes — about 50 a month. This gave me an achievable target. By the beginning of December’96 I’d already reached my goal of 600. I resisted the temptation to continue sending more out. I spent most of that month relaxing, getting organized, listening to tapes I hadn’t had a chance to get to yet, etc. I picked a number goal; your goal can be of any sort. So many of us, when doing a label, try to do too much, plain and simple. We have less time and money to put into each project — and it can all become meaningless, torturous drudgery.

My suggestion for anyone wanting to do a tape label is to put out mostly tapes by yourself or your close friends and go slowly — don’t go release-crazy. And it’s not a bad idea to take a break of a few weeks or months if necessary.

If nothing else, put the emphasis on fun, on personal satisfaction, on meaningful interactions with other hometaping artists, on the “music” itself. Otherwise, go start a rock band and send out demos and such. The point is, if you’re in this to make money, uh, well, you picked the wrong endeavor. You can take all this free advice (or tell me what to do and where to go) from someone who’s gotten burned out badly twice, and retired once for four years.”

I recall that in 1996, 1997 and 1998 Brian Noring and I dueled with who could send out the most tapes in one year. It was always a close contest. I think that the most either of us sent out in one year was something like 700 tapes.

You can view scans of the pages of HALzine #1 here

On the cover of Issue #2 of HALzine, over an obviously blown-up photocopy image of a Normal Bias cassette we find pasted the words “radical militant hometaperism”, along with the promise that inside we will find a “HALrant on hometaper personal politics and economics”.

Inside is a 12-page rant detailing my thoughts on how the cassette is the most democratic art form, what I was paying for cassettes and where I bought them, various and numerous complaints about the Fostex XR-5 4-track cassette recorder I was using, about the transition from my previous High-Bias cassette snobbism to Normal Bias cassettes (out of purely economic factors), how I dubbed my cassettes and on what gear, etc.

While admitting that “lots of hometapers out there use much different methods and equipment than mine” I go on to say that:

“there are several interconnected personal hometaper ‘political’ issues which radiate out from the points I’ve raised. I use the equipment I use for several carefully considered reasons and motivations. Also, to return to my initial point: there are reasons why I put my work out on cassettes!

Some basics: 1) I record, compose and construct (almost) all my works on cassette; 2) I use cassettes to make duplicating masters; which I then use to 3) make copies of my works on cassettes to send out to people. So, here is a basic point: from start to finish, I use cassettes. The next basic point is: I, as the artist, have control of and utilize “the means of production”. Pardon the socialist-sounding rhetoric, but this is an important point for me. I value the fact that I maintain artistic control of the audio works I produce. I try to produce works that are highly personal and are reflections of my life and experiences.”

I then go on an extended tirade against compact discs, talking about how they were essentially “consumer products” because of the high production costs, etc. One quotable quote: “I do cassettes rather than CDs for the same kind of reasons I do not own an automobile, and ride a bicycle instead”. I won’t go on here any further with a description of this rant. Suffice to say that it was written before the arrival of inexpensive home CD recorders.

HALzine #4, July 1997, is notable for its detailed report on my trip to the New York City area where I recorded with L.G. Mair, and Keith Nicolay, hung out with Doug Walker of Alien Planetscapes, recorded with Al Margolis in Brooklyn and Carl Howard in Jersey City.

HALzine #5, December 1997, reported on my October 1997 visit to F.D.R. Heaquarters in Des Moines, Iowa. You can view several pages from that issue of HALzine, as well as photos and documentation from one of the recording sessions (for the Summit cassette, featuring Charles Rice Goff III, Phil Klampe of Homogenized Terrestrials, Shawn Kerby of 360 Sound, Brian Noring and myself) here:

http://www.halmcgee.com/summit.html

All five issues contained news from other labels and ads for my newest cassette releases.

HalTapes must have also started around this time, or was that earlier?

I am not exactly sure of when I started using the name HalTapes for my label. The earliest actual document I can find bearing that name is the HalTapes Summer 1996 Catalogue. I reissued several of my older tapes plus all new material under that name. I have more or less called my label, or project of releasing music, HalTapes ever since then, even when I released compact discs or issued my music online, and even when I did compilations. I have used that name for my label activities since 1995 because that is kind of literally what my releases are.

Again, I’m assuming this was to house your own music but soon you began releasing the landmark compilation series, Tape Heads, which were huge international pan genre collections. Again, this must have been a lot of effort and expense. Did this vastly increase your international contact base? How did you put these tapes together? Just pick your favorite tracks from tapes submitted?

I produced the eight-volume Tape Heads International Cassette Compilation Series in 1998. Around that time the first compact disc recorders for home use were becoming available. At that time I was convinced that this spelled the doom of the cassette as an audio art medium. I wanted to pay what I thought was going to be one last tribute to the cassette, before it faded away altogether.

I sent out 10,000 paper leaflets through snail mail announcing and open call for the project. Anybody and everybody could participate and there was no limitation on style, just as long as they sent their contribution to me on a cassette and it did not exceed five minutes. I did not reject any contributions. Note the term “contribution”, instead of “submission”. I added the contributions to the 90-minute cassette masters in the order that they were received. I used this chance process method of determining the order of the contributions on the compilations so that no preference would be given based on any personal tastes of mine, and (as a statement) to show that I valued all forms and styles of underground cassette-based audio art, noise, and music. It also produced some interesting contrasts and connections and correlations between lots of different kinds of underground music styles. As soon as there was enough material to fill up a 90 minute tape I put out a volume of the compilation series.

A big part of the reason that I do compilation projects, and I have done several, is to find new contacts, new allies in soundmaking. The recent Dictaphonia Microcassette Compilation project brought me into contact with several audio artists who I now consider as good friends and collaborators. I also do compilation projects to assess what is going on in the scene. In the case of Tape Heads I wanted to find out just how much interest there still was in cassettes as an audio art form. Of course I always hope that compilations will help to connect artists who were not previously aware of each other. I also do my compilations to foster cross-pollination, to hopefully demonstrate that in spite of differences in style, underground music makers can find common grounds, and can learn from one another, and create new forms based on the influences and inspirations derived from other practitioners of homemade audio art.

The Tape Heads compilations contain a dizzying array of experimental and underground music styles. You never know what you are going to hear from track to track. Many of the artists are not active today, but there are many who are still around, busy, and active today. You never know what you are going to hear from track to track. See how many of these names you recognize.

Tape Heads One:

Manster, Hal McGee, Ruhr Hunter, Merrick McKinlay, Don Campau, If, Bwana, The Implicit Order, Dave Fuglewicz, The Violet Grind, Carnal Hedon Coitus, Flatline Construct (Canada), The Teleflood Project, De Fabriek (The Netherlands), Napalmed (Czech Republic), Eddy Rollin Band, Dan Susnara, Worldhate (Indonesia), Wagstaff (England), Neandertal (Italy), Concrete, HKO (USA/Canada).

You can download Tape Heads One here

Tape Heads Two:

Gruntsplatter, Expose Your Eyes (England), Ceramic Hobs (England), Brian Ladd, The End (Norway), K.D. Schmitz, E H I, Ha Ba Da, Brume (France), Art Of DEcay (Belgium), Monoid (Germany), Jeph Jerman and Dave Knott, John Netardus, Angelica Rosenthal (Italy), Diamond Shamrock, Ken Clinger, Michael J. Bowman, Maisie (Italy), Joyce Whore Not (Italy), Lord Litter (Germany), Mykee Hates Life.

Tape Heads Three:

Driving By Braile, Matt Frantz, Wrong, Stovepipe Wells (Germany), Broca’s Area, Astral Princess (Czech Republic), Charles Rice Goff III, Deleted (France), Keim vs, No (Germany), Lefthanded Decision, Ski-Mask, Chlamydia Test Cloud, Gerbil Bliss, Isomorphic Strain, The Odd Man, J mUNdoK, Bruce Atchison (Canada), Post Prandials, Lode Runner (England), M. Nomized (France), Charles Bascomb (England), Tender Love.

Tape Heads Four:

Doug Michael, Joseph Roemer, Ring (Norway), Sonic Disorder, 0781KT, Pol Silentblock (Belgium), Instagon, The Earwigs, Moth, Bruce B. Bolos, The Bran Flakes, Gaephayce, Reynols (Argentina), Odal (The Netherlands), Timo (England), A.1. Waste Paper Co. Ltd. (England), Murderous Visions, Elton’s One Man China Band, Regicide Bureau, Dave Wright

Tape Heads Five: