Kim Harten, Bliss Tapes and Aquamarine zine

Back in the 90s I received some tapes from Kim Harten who ran the Bliss label in Great Britain. I didn’t know her that well but we would have occasional contact and I was always fascinated by her label. In fact, I wasn’t even sure she was a woman because in England “Kim” can be a male name. I didn’t know how to pose the question to her at the time so, what the heck, why would it matter anyway? She did good, solid and enjoyable releases of indiepop, her main passion it seemed. Some of the artists I knew already and was glad to see they had another release on Kim’s label. Later, she started up the Aquamarine zine in hard copy form and then some years later turned it into an online zine. She has worked very hard over the years and has done quality work the entire time. And, as you will read, the fact that she is a woman makes very little difference to her although , in my opinion, she should be receiving some kudos for really being a pioneer in the underground music scene.

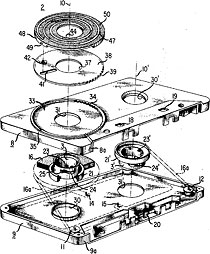

The prolific and talented Alan Davidson’s project is called The Kitchen Cynics and released this fine tape on Bliss.

Gary K released a few instrumental tapes that were quite good in the 90s. This one came out on Bliss.

When and why did you become involved in the underground tape scene?

I came to the underground tape scene via indiepop, which I discovered when a record shop opened in the town I was living in at the time that sold a lot of stuff on independent labels, such as Sarah Records and other like-minded labels. I had not previously heard of these bands but was intrigued by the minimalistic, DIY way in which the records were packaged, which was totally unlike anything I had seen before. I decided to buy Emma’s House by The Field Mice, to see what it was like, and was instantly hooked. From Sarah I moved onto other indiepop labels, and would order directly from labels like Heaven, Bring On Bull, and A Turntable Friend. These labels would put flyers for fanzines and compilation tapes in with their correspondence, and I would send off for a lot of this stuff.

The tapes I ordered, from labels like Meg, Grapefruit, KAW, Glidge, Sticky, and so on, all introduced me to lots of really great indiepop and noisepop bands. As I explored the tapes scene further however, I found that a different type of tape label existed, which was based around brutal, abstract, random noise that didn’t strike me as having much of a sense of purpose, and messily played, ultra-lo-fi songs where the sound kept dropping out and the tape hiss drowned out the songs. Noise and experimentation can be positive things when combined with melody and talent, but I wasn’t hearing any real talent here, this was stuff anybody could do, and I thought the artists couldn’t have had much pride in their creations if they were prepared to put them out in such an unlistenable state.

I was not the only person who found this sort of tape label hard to comprehend, and because labels like this existed, the entire tapes scene acquired a bad name in some quarters. Many people didn’t see DIY tapes as ‘real’ releases, and some would shun them altogether in the assumption that the tapes’ contents would be messy no-fi noise.

After I’d been immersed in the tapes and zines scene for a year or two, I decided I wanted to become directly involved. The indiepop scene was something I wanted to be a part of, and tapes were the easiest and least expensive way to release music on a DIY level back then. I also wanted to help change the bad reputation that tape labels had; whilst there were undoubtedly other tape labels putting out well-crafted music, it was sadly the messy no-fi sort that people tended to think of when they thought of tape labels. I didn’t think this was fair, as there were lots of really talented DIY musicians who were being disregarded due to assumptions that all tape labels were rubbish. In focusing on melodic, well-played, well-recorded songs, I aimed to show that tape labels can indeed exist that have a serious commitment to music and aren’t just messing around.

I wrote to some bands I’d heard on other compilation tapes and small indie-label records, asking if they were interested in being on a tape, and got enough responses that several tapes came out. The label then took off in ways I had never initially imagined, with more than 80 tapes being released over the space of around 9 or 10 years.

I noticed after founding Bliss that there were more new tape labels springing up that seemed to share my philosophy. One of my favourite tape labels was Best Kept Secret. Whilst it avoided having a ‘label sound’, its releases emphasised high quality melodic music, and Alessandro’s musical taste often overlapped with my own. I was really touched to discover from his interview elsewhere in The Living Archive that my label was an inspiration to him.

What were you doing before you got involved in your music activities?

I was a high school student.

Were you ever involved in the local scene in your area? Were you a musician yourself or ever want to be in a band?

The local scene in my area at the time was mainly metal and punk, or otherwise mainstream covers bands. Aside from one or two bands who were doing their own thing outside of all this, there was no truly alternative music scene as far as I could tell. The record shop mentioned above didn’t stay open very long as there wasn’t much of a call for real independent music in the town. Staff members told me for instance that I was the only customer who bought Sarah records on a regular basis. So no, I was not involved in the local music scene as it didn’t have much to offer indiepop fans such as myself. I had loved music since I was a very small child and had always wanted to be in a band, but this never happened as I ended up putting all my efforts into promoting other people’s music rather than making my own.

So, a tape label and a zine. Did they run concurrently? If they did, how did you manage to do both?

Yes, I started Aquamarine the year after I’d started Bliss and both ran concurrently until I called it a day with Bliss back in the early 2000s. Aquamarine is still very much an ongoing concern. I didn’t find it difficult to run both at once, as I saw them basically as two sides of the same coin.

You called your label “Bliss” and your publication “Aquamarine”…why?

Bliss is a reference to the sheer pleasure I got from music. The label’s original emphasis was on compilations, which all had colours and gemstones in their titles, and I followed the same theme when coming up with a name for my fanzine.

Was there an overriding and directing philosophy when you first started? And did it change over time?

As I came to underground music via indiepop and its various subgenres, there was an original emphasis on these styles. As I got more immersed in the underground scene, I found out about artists making music far outside of indiepop which I enjoyed just as much. Bliss was always about my personal taste in music, and I wanted to promote any music I enjoyed, not just indiepop. I don’t believe in scene-based snobbery and purism. The tapes got considerably more eclectic over time, which was potentially alienating to people who restricted their musical listening to indiepop, but I wanted Bliss to be an honest reflection of my musical taste, rather than restricting the label’s output by adhering to a single ‘label sound’.

On your web site you say you cover “folk, psych, indiepop and beyond”…is this the type of music that interests you?

Yes. I used to accept submissions from people making a wide variety of underground music genres, but got so snowed under with stuff to review that I had to make my review policy a bit more specific in order to keep my review backlog under control. I find the music I generally enjoy falls into the categories of folk, psych, and indiepop, as well as music that defies categorisation due to being a mixture of lots of genres, so I am now only soliciting review materials from artists and labels that specialise in my favourite styles of music. Whilst Aquamarine is a music zine, it’s written from a personal perspective and therefore focuses on the music I am a fan of.

You did a lot of compilations. Were they just indicative of the time period you received them…or, were they carefully crafted and curated into these collections?

A bit of both. On the whole, they simply collected music that I had received and enjoyed at the time that tape was being compiled. Sometimes I would have two or more tapes being compiled at once, in order to try and keep a general theme to the tape, so one tape would include, for example, indiepop and noisepop bands, whilst the other would be more diverse. The music on Bliss became more and more eclectic as word got around about my label and I would be sent music that was outside of my usual interests but I enjoyed nonetheless. Whilst the label began as an indiepop/noisepop label, later compilations had no real discernible theme at all, other than bringing together music that I liked.

How did you get your contacts in the pre internet age?

I would advertise my tapes mainly by flyers spread around the underground music network, and sometimes fanzines would review my tapes. Some bands would contact me as a result of seeing flyers or reviews, whilst others I contacted first as I was already a fan of their music, or because I’d seen a review of their music in a zine and thought it sounded like something I would like.

Did any of the American magazines influence you such as Option, Sound Choice, Factsheet Five, Autoreverse or Gajoob? In the publication world, whom did you regard as an influence?

The only one of these I was regularly in contact with was Autoreverse. I’d heard of Factsheet Five and Gajoob, and had possibly seen one or two issues, but they were not regular contacts of mine. I don’t recall ever coming across Option or Sound Choice. I had already started my zine before I heard of any of these publications, so they were not direct influences on its founding. Autoreverse was a zine I rated highly however, and it introduced me to a lot of great underground music.

The zines I used to read when I first started Aquamarine were all from the indiepop milieu. Most were very short-lived publications, often with just one or two issues being produced, and I can’t recall the names of many of them. One of my favourite fanzines was Scholarship is the Enemy of Romance, which was written by Chris from the band Mary Queen of Scots. I liked how he covered a lot of the music I enjoyed, and often had similar opinions on that music as I did. I also liked how his zine avoided the messy and formulaic cut and paste appearance that was par for the course for indiepop zines at the time. Whilst I never set out specifically to copy this fanzine, I think it’s fair to say that I was at least subconsciously influenced by it to a certain extent.

Zines I enjoyed that came along later included Circle Sky and The Original Sin, among many others. My favourite type of zines were the ones that dug deep into the underground, but without espousing an ‘indie snob’ mentality.

How long did you do a printed version of your zine?

Between 1994 and 2000, when Aquamarine became a webzine

How did the internet change what you do?

It made things a lot quicker and cheaper. I no longer had to buy stamps and post letters in order to contact people. I no longer had to print out hard copies of fanzines. I could post reviews and articles on my website as soon as they were written, rather than having to wait for a whole issue to get finished before getting the word out about the music I’d featured. So the internet has made fanzine writing rather more convenient.

Having a website also meant far more people got to know about my zine, and the music I was promoting was potentially reaching a much wider audience than when Aquamarine was a paper zine.

Do you think the internet is inherently superficial and impersonal?

Back in the ‘old days’ there was a tendency for fanzine people to write detailed and frequent letters to each other. They would strike up long-distance friendships with each other which would sometimes develop into real life friendships. These days, internet based communication tends to be a lot briefer, with less in-depth conversation, and it’s also become more normal for people to read an online publication but not bother contacting its writer. It seems there is less opportunity for people in the underground scene to really get to know each other now, as communication styles have changed so much. This has its advantages and disadvantages. If I was writing detailed correspondence to lots of contacts, this would leave me less time for actually reviewing music. Yet not getting as much correspondence from readers these days sometimes makes me wonder whether anyone is actually reading Aquamarine or if I’m just shouting into the ether.

In the pre internet days, there were some women in the underground, home taping scene…some, but not many. Sometimes they were just the lead singer in an all male band. And now women play a vital role in today’s alternative music and art scene. Thankfully there are more women than ever expressing themselves in creative and unusual ways. Can you talk about why this changed, if you think it did?

This is a difficult question to definitively answer, and I can only offer some observations. No-one was stopping women from getting involved in underground music. I don’t buy into the extreme feminist notion of a ‘patriarchal conspiracy’ preventing women from participating in the interests that appeal to them. Women, at least in the parts of the world that have a thriving alternative music scene, have been free to make their own choices in these areas for a long time now, and it is evident that they were, in the most part, choosing not to become actively involved in cassette culture.

I really don’t know why this is. One possible explanation could be because tape labels had acquired a ‘geeky’ reputation in some quarters. You name a ‘geeky’ interest area, whether comics, sci-fi, computers, or anything involving collecting and cataloguing things, and you will find most of the people who profess an interest in these topics are male. Some have asserted that there is a biological reason for this, that these sort of interests are more in line with the way the male brain works. Otherwise it could just be that women often don’t take kindly to being called geeks, and avoid pursuits that could cause them to be stigmatised in this way.

I remember a handful of female-run tape labels back in the 90s but they were not only very few but tended to be very short-lived. There were more female fanzine writers; maybe a quarter to a third of the zines I read were written by women, but again they tended to be quite short-lived projects. These women would try out underground culture for a while but then realise, for whatever reason, that it wasn’t for them. I must stress however that losing interest in direct involvement in underground music is far from being an exclusively female trait; many of the men running indiepop-oriented fanzines and tape labels gave up after putting out just a few issues or releases. What is true however is the longer-lived, musically eclectic tape labels with a large catalogue were pretty much all run by men. I however wasn’t only a rare example of a female underground music promoter but one who has stuck at it for more than 20 years.

Much of the female involvement in underground music that I remember from the 90s was motivated by feminist politics. There was a lot of talk of running labels or zines, or forming bands, just to prove a point that ‘women can’. Although I’m female, I found this sort of thing alienating rather than encouraging. I never needed any political manifesto to motivate me into starting a label or zine. I never saw my gender as an issue; I was just a music-loving human being who wanted to share the music I loved with other music-loving human beings, regardless of gender. I never experienced any sort of misogyny or discrimination for being a female tape label owner or zine writer; most of the people I was in contact with also didn’t see my gender as an issue.

I hated the anti-male politics that were such a big thing in the Riot Grrrl scene. Whilst this scene was all about encouraging women to get involved in music, perhaps many women found its in-yer-face politics offputting, ironically producing quite the opposite result from what the scene had set out to achieve.

It seems more women are becoming involved in underground music these days for the music itself, rather than being motivated by a form of politics that sees the participants’ gender as more important than the actual music they are making or promoting. This is the way it should be. For me it was always about music, not political sloganeering.

Many of the artists in your catalog have disappeared from the radar. Have you made a conscious attempt to revive communications? Have you been able to re-establish contact with some artists?

As a general rule, I’ve not made any real effort to track down old contacts. For a lot of people, music and fanzines were a hobby they had 20-odd years ago but they’ve since moved on to other things. Sometimes I will find a website of an old contact, usually quite by chance, and see that they are still involved in music. On these occasions I might drop them a line regarding their current projects. But with people who have since given up music, I suspect they would probably be bewildered or even annoyed at people getting in touch with them about stuff they did years ago that they no longer attach any significance to, so I have not seen any legitimate reason to re-establish contact with people who are no longer active in music.

What is it that rewards you personally about doing what you do?

Discovering new music that I really enjoy, that I would never have known about otherwise. Being in touch with like-minded people who share my musical interests. Having met my long-term partner via the underground music and zine scene. Getting involved in underground music has changed my life in many ways, and I can’t imagine not being a part of the underground music world.

What’s next?

Aquamarine #28 is currently in progress and can be found here

So far I have articles on Fruits de Mer Records and Music & Elsewhere’s Decadion 2 compilation, and reviews of assorted folk, indiepop and psych releases, though much more will be added over the coming months.

Best way to contact you?

Via the email address found at the foot of the homepage

Thanks and good luck Kim.