The Handmade Tale: by Kathleen McConnell

I was at a party at my friend Geoff’s house and ran into a woman who had done research and a report on Cassette Culture some years earlier. We both thought it odd and a happy co-incidence because hardly anyone knows about this subject at your regular party. Of course, parties at Geoff’s house are particularly interesting and enjoyable and it was my good fortune to meet Kathleen and get her permission to republish her work.

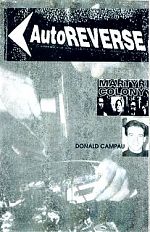

The tapes pictured are from my collection ( Don Campau)

Reprinted by permission of the author and originally published in The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest ed. Ian Peddie (Aldershot etc.: Ashgate, 2004), pp.xxx-xxx. Copyright [copyright symbol] 200X.

My thanks to Kathleen McConnell for allowing republication of this article.

Emerging directly from the ashes of OP magazine, Option was published by Scott Becker in Los Angeles.

Introduction by Kathleen McConnell

In the mid-nineties, I ran the Show-Off Gallery in Bellingham, WA with my pal Lars Holmstrom. When we inherited the space from Connie and Eric Owstrowski, the Show-Off had been hosting all-ages music and art events for about five years. Inspired by the X-Ray Cafe in Portland, OR where I grew up and the music and zine scene in Olympia, WA where I attended school, my dream was to offer an open stage to anyone who had something to say. I had a very democratic vision and thought of the Show-Off as a live, on-going work of public art akin to Group Material’s 1980s “Democracy” project. Because I also lived in the Show-Off (a former warehouse), art and everyday life blurred together. My living room was a stage painted blue and my claw foot bathtub hosted several art installations. (For a great history of the Show-Off, listen to Clyde Petersen’s podcast “The Sea-port Beat: Episode 5: The Show Off Gallery” hosted by Hollow Earth Radio: http://hollowearthradio.org/podcasts)

By the time we passed the Show-Off over to Cory Brewer, I was disappointed with the NW indie music scene, which seemed to be interested mostly in branding and band promotion. I went back to school and found in cultural theory a vocabulary that allowed me to organize my disappointment into a critique. I also found an amazing archive in Bowling Green State University’s popular music library.

By some small miracle, all twenty-six enchanting issues of the Lost Music Network’s Op magazine had found their way from someone’s (Robin James?) parent’s garage in Michigan to the stacks at BGSU in Ohio. Or that’s how I remember the story. John Foster launched Op in Olympia, WA in 1979 and though I’d lived in Olympia for four years I’d never heard of it. I felt like I’d found a kindred spirit. Each issue of Op featured a collection of stories about independent musicians, events, and practices loosely bound together by a common letter (issue “A” covered Laurie Anderson, a cappella, and the Alabama sound). It was a makeshift cataloging system for phenomena that didn’t yet have a grammar. And the idea behind the project was to give everybody’s music project a stage regardless of format, genre, or renown.

I became particularly interested in Graham Ingels’ regular column “Castanets” in which he reviewed whatever home-recorded cassette tapes folks sent him. “Castanets” was a remarkable labor of love. Having witnessed firsthand some of the strange, often conflicting, and sometimes incoherent motives that people bring to an open stage (part of the beauty of such forums), I was truly impressed with the patience and regard Ingels showed every project.

“The Handmade Tale” is my attempt to explain what I found so amazing about Op, and until recently I thought I had written a history of a lost past. Then I met Don Campau at a backyard party in San Jose, CA, stepped into his living archive, and was reminded of why I once thought independent art had something to do with democracy.

The handmade tale: cassette-tapes, authorship, and the privatization of the Pacific Northwest independent music scene by Kathleen McConnell.

Though the Earth, and all inferior Creatures, be common to all Men, yet every Man has a Property in his own Person: this no Body has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the State that Nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his Labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his Property. (Locke, 1960, p. 305)

The emergence of a cassette culture

In the early 1980s the International Federation of Phonogram and Videogram Producers launched a campaign for a blank tape levy with the slogan ‘Home- Taping is Theft’ .At the same time the Recording Industry Association ofAmerica (RIAA) printed the slogan ‘Home Taping is Killing Music’ on all their materials in an effort to respond to the perceived threat of new and increasingly popular home recording technologies (Frith, 1987, p. 60). These campaigns targeted two different activities: the dubbing of commercial music, which eroded industry profits, and the practice of home recording in which individuals recorded audio texts using consumer cassette decks. With the advent of the home cassette deck with recording capabilities, any consumer could potentially be an audio pirate or a recording artist, and a network of home recording enthusiasts did in fact exist, united under the banner of ‘independent music’ . With the advent of the affordable and convenient consumer cassette deck, the cassette-tape became emblematic of the potentiality of independent music and a cassette culture emerged that championed the use of home-based recording technologies thus challenging the RIAA’s allegation. The culture of independent music supported the proactive, do- it-yourself musician, rejected the perceived homogenization of mainstream music, and challenged the property rights that music corporations enjoyed over cultural resources. Enthusiasts hailed independent music, especially cassette-tape recordings, as a ‘new model of cultural interchange’ that challenged the ‘ideology of copyright’ and provided an ‘activity available free to all’ (McGraith, 1990, pp. 83-87).

In the American Pacific Northwest, an independent music scene first took shape in the late .1970s with the rise of interconnected activities such as home recording, small press music journalism and live music shows hosted in private homes or small venues. Olympia, Washington was a particularly notable site of independent music practices (Humphrey, 1995). It was there that the Evergreen State College radio station, KAOS, implemented a policy requiring that 80 per cent of all music played on the station be produced by record labels other than

the six big music corporations. In 1979 the person responsible for that policy, John Foster, founded the Lost Music Network and launched a small press publication about independent music called Op, which resulted in the catchy acronym LMNOP. Two of Op’s contributors, Calvin Johnson and Bruce Pavitt, recorded local bands and distributed cassette-tape compilations under the respective names of their new record labels: K Records and Subpop.l Around the same time, a music venue called the Tropicana opened on Olympia’s main street and hosted bands such as Calvin Johnson’s Beat Happening, Rich Jensen’s The Wild Wild Spoons, and The Young Pioneers. This small network rejected the homogenizing tendencies of mass-produced culture; and the corporatization of everyday life in favour of the crafted artefact and singular

experience. The first major overhaul of US copyright law since 1909 coincided with these activities. Among other significant revisions, the US Copyright Act of 1976 granted authors copyright protection for their work from the time a text was ‘fixed’in tangIble form, thereby no longer requiring individuals to register works with the US Copyright Office. In the spirit of John Locke, this revision established the act of creation as the basis for ownership over a text. The authorship granted by US copyright law resulted from a 400-year-old legal discourse that first emerged in tandem with printing technologies and the book trade in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (M. Rose, 1994), and it is this discourse that later allowed independent musicians in the Pacific Northwest to sign their name to audio texts and thereby claim authorship of their work. After the 1976 revisions to the legal code the law would formally recognize their signature as such a claim. These cultural and legal shifts further naturalized the now common-sense notion that an individual could declare a particular

grouping of words, images or sounds as their private property, which served to further privatize cultural resources.

Home recording and cassette culture, which entailed not only the recording and listening to, but also the trading and documenting of, cassette-tapes, dovetailed with the concomitant rise of other independent music practices.

Cassette-tape enthusiasts shared a general dislike for mainstream music, an indifference to sound quality, a passion for singular experiences, a preference for limited editions over mass-produced copies and an interest in dO-it-yourself music projects. In addition, they lauded originality and sincerity over the presumed :filters and glitz of mass-mediated music. In their home recording endeavours, they protested copyright law while simultaneously employing rigid notions of originality in order to establish authorship and ownership of the texts they created. Inspired by the emergent technologies of home recording, cassette- tape enthusiasts defined original as ‘homemade’ and ‘handmade’ texts and demarcated a space of independent music distinct from the mainstream music industry. The initial passion for all audio recordings along with the celebration of home recording practices as a ‘democratic art form’ eventually gave way to standardization within independent music and uniformity across localized scenes (McGee, 1992, p. Vlll). Cassette-tape enthusiasts and other independent recording artists forged cultural logics required to appreciate their creations, which resulted in the formation of a conceptual space accessible only through appropriate knowhow. In this way, home recording technology was used to exercise the historical function of authorship and limit ‘the cancerous and dangerous proliferation of significations within a world where one is thrifty not only with one’s resources and riches, but also with one’s discourses and significations’ (Foucault, 1984, p. 118). Home-based recording artists associated authorship with individual ingenuity and employed notions of authorship to fashion privatized texts and constrain, via exclusion and choice, a proliferation of interpretation. Despite their general hostility towards copyright laws, cassette- tape enthusiasts fixed audio texts with a private preferred meaning over which individuals claimed ownership.

The reviews of cassette-tape projects in three music-related, small press publications provide evidence of the shift from an initial celebration of a democratic art form to an eventual Pacific Northwest music scene. Op, Sound Choice and Snipehunt all featured articles, interviews and reviews about independent music, including home recording projects. Circulated in succession, they collectively span a period of 17 years between 1979 and 1996. Op was the pioneering publication that ran from 1979 to 1984. Like Op, Snipehunt was Pacific Northwest-based with an editorship in Portland, Oregon. The quarterly first started as a fanzine in 1988 and ran until 1996. Sound Choice, which ran from 1985 to 1992, was California-based but featured Pacific Northwest writers and musicians. The reviews featured in these publications established the criteria for originality within the independent music scene and helped readers adopt the appropriate sensibilities for the appreciation of independent music. The reviews of cassette-based projects offer a narrative that illuminates why home recording technology was adopted, what the cassette-tape in particular allowed that could not be done with other audio technology, and the aural and visual qualities associated with these projects. The earlier reviews, in particular, captured the spirited excitement for the potential of the relatively new phenomenon of home recording technologies.

Home recording technology eventually succeeded only after several decades of failed marketing strategies in which manufacturers and retailers attempted to forge an association between the home phonograph and the camera by selling sound recording as an artistic hobby akin to amateur photography (Morton, 2000, p. 138). Despite these efforts, the most popular use of recording technology proved to be the reproduction of eight-tracks and cassettes, and by the 1960s 90-minute blank tapes were available which allowed the recording of an entire LP. By the late 1970s the standardized and increasingly affordable home cassette deck, car stereo or Sony Walkman made audio technology ready to hand for consumers. Consumer audio technology allowed for small-scale production as well as listening, and also provided a way of personalizing or individualizing musical tastes; for this reason, the cassette-tape simultaneously represented methods of mass production as well as customization. While Pacific Northwest

musicians, such as Beat Happening who released their first recordings on cassette-tape, were in some ways exceptional in their enthusiasm for cassettes, they were making use of technology that was, by 1980, a commonplace feature of the everyday landscape (Azerrad, 2001, p. 465). Pacific Northwest recording artist Cory Brewer, for instance, used his parents’ stereo equipment to ,start a cassette-based label featuring Botan Rise Candy, The Shitsters, Sunday Driver, Bland, and Chrysler Stuart and the Stewardesses: ‘Almost all of the stuff that t put out…was just recorded on the hand-held, low-fi tape recorder. .. [copies were made] on my parents’ tape deck; I would just sit for hours on end and I would just put it on high speed dubbing and watch television while I was doing it’ (Brewer, 2002, personal interview).

As with any technology, the cassette deck required a particular knowhow, and its everyday uses in tum acquired an ethos. Cassette-tape enthusiasts cultivated this knowhow and drew a distinction between the common audio technology user and the cassette-tape connoisseur. In order to establish such a distinction, cassette-tape enthusiasts negotiated and modified legal discourses concerned with music pirating. In addition to extending legal protection to sound recordings, the Copyright Act of 1976 had codified fair use doctrines. The 1976 Act, however, did not extend fair use to the burgeoning, non-commercial practice of home-based audio dubbing. The legal discourse regarding the dubbing of music intersected with cassette culture in two places: first, anywhere an individual copied or ‘pirated’ an audio text, in which case the individual was either knowingly or unknowingly technically in violation of the law; second, anywhere cassette-tape enthusiasts employed the notion of authorship, in which they knowingly or unknowingly borrowed legal constructs in order to establish criteria for what constituted an original text. A letter to the editor of Sound Choice gives a sense of the degree to which cassette-tape hobbyists were aware of copyright law, and how they perceived it to affect their own recording practices as well as the distribution of music:

And while I must confess to buying an occasional bootleg album, I have no respect whatsoever for the parasites who manufacture and distribute unauthorized products. The record companies’ stance is clear, altho~gh at times some ,of the legalities get blurry. (Is [it] legal, for example, to tape a live show off the radio then make a copy for a friend?) My experience with tape traders leaves me with the impression that most are highly ethical and are simply fanatical fans and collectors of music, even given some of the possible contradictions involved. (A bootleg album, for example, must of necessity originate from somebody’s tape …) (Mills, 1985, p. 8)

The extent to which the letter writer engaged the technicalities of the law was not exceptional. The criminalization of dubbing practices prompted a need for a clear definition of originality in order that individuals could distinguish, if to no one but themselves, the difference between audio projects that involved copying, and those that were singular creations. ,Dan Fioretti offers an example of this distinction in his how-to essay for potential cassette-tape enthusiasts titled ‘What Do You Do With Them Tapes’? He suggests that there is more to home recording than just dubbing:

The very next thing you could do with cassettes is use them to make nic~ li~e original noize [sic] … [let] us say right now that not all blank tape purchased i l l this country is for the use of recording copyrighted m.aterial-that not. everyone buy~ a blank C-60 or C-90 just so they can tape a Bon J O V l LP or tape therr fave toonz [SIC] off the radio … I remember when me and all my cousins and my two sisters and. brother would get together and do weird audio tapes. We even did a parody of The Brady Bunch once! (Fioretti, 1992, p. 19)

Where the letter writer above drew a distinction between the retailer who pirated copies for profit and the enthusiast who dubbed a radio show for a friend, Fior~tti drew another between the reproduction of an existing audio text and the creatIOn of a new text. This second distinction was essential to cassette culture, which expanded the definition of originality to include captured sounds as well as th~se that were intentionally constructed. For instance, another cassette-tape enthUSIast suggested using cassettes ‘to record things that have never been recorded before. Just what does a bowling alley sound like? What did your kid sound like when she was born? What happens outside your window while you are at work?’ (Jenson and Robin, 1992, p. 41). In this case, the distinction is between recording an original audio text such as a newly composed song, and capturing an original act of expression that is original in the sense of its moment of inception, such as a child’s first words. A fascination with this last distinction is perhaps what most set apart the early reviews featured in Op from later reviews featured in Sound Choice and Snipehunt.

The Lost Music Network, Op magazine, and the ARCs of independent

music

The Lost Music Network (LMN) published 26 issues of Op, one for each letter of the alphabet before discontinuing. According to Op editor John Foster, the motivation for the project was an altruistic desire to network musicians with potential listeners. As he explained in an early editorial:

I want to help independent artists and labels be heard by people who would like them. I want people with an interest in certain types of music to be able to <Tet in touch with each other. I’m not very interested in being a critic, but I want to se~and hear what other people are doing and thinking (Foster, 1980, p. 1).

For Foster, music corporations enjoyed too much control over people’s listening practices despite a proliferation of independent music recording, and his mission was to make obscure music accessible: ‘We think you should have a greater opportunity to fInd out about music out of the mainstream’ (Foster, 1982, p. 1). In this sense, the Lost Music Network was an explicitly political project that challenged corporate control over music. When Op was launched, there was nothing qnite like it, and Foster’s project was ambitious: to document all projects by musicians practising outside the corporate music industry. Since there was no precedent, any catalogue system of the independent music scene was a sta.rt:i.rlg point, and LMN started with the first letter of the alphabet. Issue ‘A: featured reviews of, interviews with and information about musical projects that started with the letter A, such as Laurie Anderson, the Alabama sound, and a cappella. Beginning with issue ‘F’, Op reviewed cassette-tapes separately from vinyl in a column called ‘Castanets’, by Graham Ingels. The purpose of ‘Castanets’ was to ‘introduce the reader to the wide and wonderful world of cassettes – the ultimate in decentralized production, manufacturing and distribution’ (Ingels, 1981a, p. 3). Ingels’ reviews offer a glimpse into an emerging cultural phenomenon for which there was yet no standardized language: ‘[This cassette-tape] is poorly recorded,

live, conjuring up a vision of a place where performances only takes place behind closed doors’ (Ingles, 1984a, p. 17). His main objective was to document the new phenomenon of cassette-based home recording, and he drew from the values of cassette culture to establish criteria by which to judge projects ‘recorded in living rooms and basements’ (Ingels, 1984a, p. 16). He always noted, for instance, captured or ambient noise: ‘[This tape] has some fascinating things done with ambient sounds recorded in and from Perkins’s apartment’ (Ingels, 1981b, p. 8). He also praised spontaneity and other evidence of home recordings: ‘this 3-song cassette EP includes … a piece recorded underwater, and a recorded prank phone call that was very disturbing to listen to’ (Ingels, 1983, p. 19). Along with the aural appeal of ambience and spontaneity, Ingels valued the exclusivity, ‘home- made styles’, and obscurity of these projects (Ingels, 1984b, p. 11). Frequently he noted handmade covers suggesting the artist had made an extremely limited number of copies and perhaps no two copies exactly alike: ‘Nice clear folky home-made songs in handsewn pouch with a little book of song titles, words, and pictures’ (Ingels, 1984c, p. 18).

Ingels’ descriptions of homemade and handmade projects contrasted sharply with the recordings he described as ‘polished’, ‘professional’ or ‘squeaky-clean’. Within the logics he employed to ceiebrate ‘homemade styles’ and to disparage ‘polished’ recording techniques, Ingels’ forged an association between the physical cassette-tape and the individual who recorded sounds on to it. The sounds on a tape were the unique expression of an individual regardless of the origins of the sounds captured in the recording. Consequently, his reviews reinforced the now common-sense notion pioneered by John Locke that a person’s ‘astigmatic recasting’ of cultural resources was the private property of that person (Litman, 1990, p. 1012). In this way Ingels extended the established notions of authorship to the practices at play in cassette culture.2 While Ingels and other cassette-tape enthusiasts recognized the dubbing of music to be a legal issue, it is not clear that they recognized notions of authorship as such. Cassette- tape connoisseurs’ celebration of the homemade and handmade sensibilities emblematic of the do-it-yourself musician not only challenged corporate control over musical production and ‘distribution, but also seemingly challenged the copyright laws that rationalized that control. Cassette culture did not, however, subvert or resist the logics of intellectual property rights so much as fortify the historical function of authorship. The cultural logics employed by Ingels to establish the value of home recording artists drew from legal discourses now naturalized into civil society. These discourses were the reason why cassette-tape enthusiasts could appreciate all recorded sounds, including ambiance, voices in the background and the inadvertent squeak of an instrument as ‘authored’ by a person. Legal discourses informed musicians’ abilities to claim audio texts as private property, a claim that was implicit each time an individual or band recorded sounds and then signed their name to the recording. The protocol of crediting individuals undermined efforts on the part of the Lost Music Network and cassette-tape enthusiasts to democratize music practices, although establishing musicians’ credentials was less of a priority for Op than was the distribution of information. This changed as PacifIc Northwest bands grew in popularity and a PacifIc Northwest independent music scene began to take shape.

Sound Choice and the rise of the author in independent music

As Foster had planned from the outset, Op did indeed discontinue after 26 issues, despite objection from its subscribers. With the same pragmatic tone of his earlier editorials, Foster opened issue ‘z’ by redirecting readers’ attention to new projects that aspired to pick up where Op left off. Two publications in particular, both California-based, positioned themselves as the Op legacy: OPtions and Sound Choice, published by the Sonic Options Network and Audio Evolution Network respectively. Sound Choice, based in Ojai, California, and fIrst publishedinthespringof1985,identifIeditselfastheless’glossy’ofthetwoand more in the spirit of Op. Like Op, Sound Choice lauded home recording and cassette culture. With their fIrst issue subscribers received two cassette-tapes that represented ‘artists who have taken control of their audio explorations from start to fInish preserving the unique, interesting, provocative or idiosyncratic nature of their art as expressed through the cassette medium’ (Sound Choice, Spring 1987, p. 6). Despite these similarities, Sound Choice marked a signifIcant departure from the motivations of the Lost Music Network. This shift reflected broader changes within independent music practices. As independent recordings became increasingly accessible, the preservation of authorship became an overriding priority for the magazine as it did for the musicians who submitted their recordings. Whereas Ingels reviews typifIed a genc:ral fascination for recorded sound, Sound Choice reviewers focused their attention on who authored the texts. Despite their commitment to cassette-tape enthusiasts, Sound Choice was also not quite as democratic as Op in its reviews policy, as the publication primarily focused on the offerings of independent labels. Although Sound Choice encouraged home recording and reviewed individual submissions, its review section reflects the growing centrality of a label-oriented music scene. With formated columns and illustrations that corresponded to the texts, even the layouf of Sound Choice adhered to more conventional magazine practices than had Op. Up until the 1989 Fall issue, the magazine alphabetized reviews by artist or project name, but beginning in the autumn of 1989, the pUblication changed the format of the review section and listed all projects by musical genre. The shift away from Op’s pioneering catalogue system suggests increased standardization of independent music practices.

When preservation of a music scene took priority over making music, independent recording artists and reviewers increasingly employed notions of originality and authorShip to protect their audio texts. While Sound Choice reviewers adopted the homemade and handmade criteria for originality and authorship established in Op, their reviews modifIed these notions. Reviews in Sound Choice frowned upon unoriginal material such as covers, and although it was customary to acknowledge influences on a musician, reviewers distinguished between influences and what they considered to be mere imitation. The standards for originality in home recording had changed, and Sound Choice reviewers expressed a sarcastic frustration with what appeared to be a tape of collaged sounds: ‘Let’s cut up some tapes of fundamentalist preachers recorded off the radio and TV! This is not a particularly new idea in 1986. And the less well it is actually done, [the] older and staler it sounds’ (Sound Choice, Wrnter 1987, p. 45). For Sound Choice reviewers the novelty of home recording had diminished as had experiments with captured ambiance. A cassette-tape entitled Idiot-Savant: Live 86’d that might have fascinated Ingels was dismissed by Sound Choice reviewers as insignifIcant: ‘More idiot than savant and more eighty-sixed than live. This is mostly a tape of a bunch of people fooling around, presumably in their garage. There was apparently no attempt to do anything here but turn on a tape machine and record whatever happened. Nothing did’ (Sound Choice, Wrnter 1987, p. 53). By the evolving standards of independent music, to simply turn on the tape recorder and capture some sounds no longer qualifIed someone as an artist, nor did using commonplace home recording technologies. The fact that anybody with a cassette deck could record an album was no longer sufficiently compelling reason to document home recorded projects. Despite this shift, Sound Choice reviewers continued to note homemade and handmade qualities, although the term ‘homemade’ began to refer to attributes other than where the recording was made. In some instances, reviewers used the term unfavourably to indicate that the recording sounded cheap, as in the review of the band Balcony of Ignorance: ‘Sooner or later there had to be a dark side to the record-it-at-home, do-it-yourself ethic this magazine promulgates… Sooner or later people with absolutely no talent at all were going to start making tapes of zero quality. And here it is … Probably recorded on a cheap walkmate style recorder’ (Sound Choice, Spring 1986, p. 37). Another review chastizes the artists for using recording technology that, by the mid-1980s, was outdated: ‘Much of this tape is very poorly recorded which seems inexcusable with all the adequate, inexpensive recording equipment in this day and age’ (Sound Choice, Spring 1986, p. 63). While Sound Choice reviewers disparaged cheap home recording technology, the term ‘homemade’ maintained a positive connotation as a reference to a particular kind of musical sensibility bearing little relationship to where or how the recording was actually made. Musicians could now affect ‘homemade’, and reviewers used the term to mean sincerity, as in: ‘There is an under produced, homey, personal touch to all this’ (Sound Choice, Wrnter 1987, p. 53). The term ‘homemade’ and related terms such as ‘DIY’ or ‘low-fI’ that at one time referred to particular production methods now referred to an aesthetic and style of music that came to defIne the PacifIc Northwest independent music scene.

Towards the end of its run and with the eventual change in the review section format, Sound Choice all but ceased reviews of home recorded cassette- tapes. PacifIc Northwest cassette culture had lost two network hubs in Op and Sound Choice.3 In addition to the loss of small press resources for cassette- tape projects, Sub Pop and K Records began to release their recordings on vinyl and compact disc, as did the small forest of independent labels that had sprung up in the PacifIc Northwest in the 1980s. Despite these changes, the notions of originality, ‘low-fi’ aesthetics and rejection of mainstream cultural enterprise that had emerged in tandem with the rise of cassette culture continued to influence a general sensibility around which a PacifIc Northwest scene was organized.

Towards the end of its run and with the eventual change in the review section format, Sound Choice all but ceased reviews of home recorded cassette- tapes. PacifIc Northwest cassette culture had lost two network hubs in Op and Sound Choice.3 In addition to the loss of small press resources for cassette- tape projects, Sub Pop and K Records began to release their recordings on vinyl and compact disc, as did the small forest of independent labels that had sprung up in the PacifIc Northwest in the 1980s. Despite these changes, the notions of originality, ‘low-fi’ aesthetics and rejection of mainstream cultural enterprise that had emerged in tandem with the rise of cassette culture continued to influence a general sensibility around which a PacifIc Northwest scene was organized.

Snipehunt and the privatization of the Pacific Northwest music scene

In the early 1990s what were still obscure and disparate practices in the Pacific Northwest that were loosely identified under the banner of independent or alternative music received widespread media attention, coalescing those who wished independent music to remain as distinct as possible from mainstream popular genres. As the notoriety of the Pacific Northwest independent music spread, those who identified with it fashioned conceptual boundaries around associated texts and practices and insisted that appreciation of independent music required the mastery of particular culture logics. As Will Straw suggests, the significance of these logics is ‘neither in the transgressive or oppositional quality of musical practices’ but in the processes ‘through which particular social differences … are articulated within the building of audiences around particular coalitions of musical form’ (Straw, 1991, p. 384). The Pacific Northwest independent music scene is, then, significant not because it challenged the homogenization of popular music or democratized musical practices, but because it produced a new musical aesthetic, appreciation of which was more than matter of merely opening one’s ears and simply listening. A person’s ability to determine

the significance of any given cultural artefact, and thus appreciate it, requires consciously or unconsciously learning the knowledge, language or ‘internal logic’ available to name it (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 2). The ability to register a giv~n text as representative of a particular author is dependent on the reader’s or listener’s mastery of relevant modes of perception: ‘to see (voir) is a function of the knowledge (savoir)’ (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 2). At the same time, the pleasure of appreciation is also an act of forgetting the acquisition of cultural skills so that the experience of listening to low-fi punk, for instance, is perceived as sublime. In short, the text seemingly transcends cultural impositions. Bourdieu suggests that all forms of culture, including popular culture, require a particular knowhow to navigate them ‘properly’, but mastery of the skills effaces the learning process and conceals the acquisition of cultural logics. More than either Op or Sound Choice, the quarterly newspaper Snipehunt was most explicit in defining what constituted the proper cultural logics for appreciation of the Pacific Northwest independent music scene.

Printed in duo-toned colour on newspaper and freely distributed to coffee shops, record stores, theatres and nightclubs, Snipehunt featured as many comic strips as it did reviews and was a miscellany on scene-related endeavours such as Stella Mars’ postcard art. Although reviewers did track musical phenomena outside the Pacific Northwest, Snipehunt was most dedicated to regional music and each issue featured ‘scene reports’ from a handful of Pacific Northwest towns. In her regular column titled ‘My Eye’, editor Kathy Maloy stated her goals for Snipehunt, which extended beyond merely providing music news and information: It’s not enough anymore to tell people what kind of music they should listen to. I want to tell people how they should live their lives. Information that is useful like where to buy your food, how to fix your bicycle and how to make the first move and still smash the patriarchy. Real life matters not rock journalism. (Maloy, 1996a, p.4)

For Maloy, punk rock was not just a musical genre, but a way of life explicitly positioned in opposition to all things corporate, from corporate jobs and corporate clothes to corporate music and corporate media, a sentiment she shared with her predecessors at Op and Sound Choice. However, rejection of mainstream culture took a different turn in the pages of Snipehunt. Whereas John Foster rejected the homogenizing tendencies of mainstream culture by encouraging a proliferation of music-making, Maloy wished to preserve the private preferred meanings she assigned to independent musical enterprise and, in that way, protect Pacific Northwest independent music from becoming itself homogenized. Increasingly, Maloy felt that the popularization of independent music threatened her way of life, and she expressed fears about the encrpaching masses that had suddenly arrived on the scene. ‘What I am most afraid of is that people who don’t even live here are coming to make money at the expense of a cute little scene that has thrived so nicely in its semi-obscurity’ (Maloy, 1995, p. 6). Maloy linked her anxieties to the fear that people might not ~espect the proprieties of her scene: ‘Portland is changing. People are movmg t.o my

community. Will they know how to behave when they get here? Will they live up to my code of behaviour?’ (Maloy, 1996b, p. 7).

In the face of such threats, the fascination with home recording technologies characteristic of earlier independent musical endeavours all but disappeared while notions of authorship did not. There emerged a band-focused style of journalism that sought to establish credit and credentials as well as demonstr.ate mastery over the cultural logics used to exercise judgement: Only ongomg musical projects with a signature style such as Hazel, Bugsklill, New Bad Things, Irvincr Klaw Trio and Unwound made the Snipehunt charts as the emphasis shift:d from playing music to establishing a name.5 Whereas Op and Sound Choice defined the term ‘independent music’ broadly to include a variety of musical genres such as jazz, new age and, in effect, all non-major label recordings, Snipehunt focused on the subgenres of punk and rock ‘n’ roll. In addition, Snipehunt did not discriminate between ‘independent’ and ‘major’ labels in their feature articles or reviews and had no policy against reviewing

‘demo’tapes (Op and Sound Choice refused). Reviewers noted the format of recording projects (for example, seven-inch vinyl, full-length vinyl or cassette- tape), but there was no longer a dialogue about the advantages of cassette-tape projects versus vinyl-based recordings. Instead, the cassette-tape came. to represent an early stage in an artistic endeavour rather than a respec~bl~medIUm in its own right. Small labels, such as Union Pole, released compilanon tapes until they acquired enough capital to release projects on vinyl. Snipehunt reviewers still used terms such as ‘DIY’ and ‘low-fi’, but ‘homemade’ rarely appeared. The primary difference between Snipehunt reviews and those in Op and Sound Choice was their intention.

The purpose of Snipehunt was not to make independent music accessible, but rather to police the property lines of the bands that constituted the scene. Snipehunt was so band-oriented that the handful of reviews of cassette-tapes assumed the recordings to be merely one aspect of a larger effort to establish name recognition: ‘I wonder what the band’s live show is like. There’s not a lot of originality on this tape’ (Anonymous, 1992-93, p. 36). Unlike Ingels’ reviews that considered the cassette-tape itself to be significant, the Snipehunt reviewer saw the tape medium as wholly unrelated to the band’s project-At the same time, Snipehunt reviewers employed the cultural logics forged in part by Ingels. ‘They heard recordings, regardless of the actual source of the sounds, as the organic self-expression of the musician and, by these cultural logics, it made sense to speak of an artist’s‘own voice’ coming through on the recording: ‘I hope that this is just the start for the Dharma Bums, that they are now coming into their own with the confidence to do and say what they want in their own voice’ (Anonymous, 1992, p. 41).6 In the hope that the Dharma Bums spoke ‘their own voice’ lay the implicit notion that such a voice was possible.

As the Pacific Northwest scene crystallized, the appeal and usefulness of the cassette-tape faded as artists no longer needed to record at home in order to express originality and sincerity. Consequently, reviewers treated the rare mono reel project, such as Sid Merrt’s home recorded project, like a relic – impressive if only because anyone still used it: ‘This cassette was recorded over the course of four Saturday night “salons” at Sid Merrt’s southwest Portland apartment …All of these songs were recorded on a mono reel to reel using only one microphone, yet the sound is quite impressive…This is more than a music cassette; it’s a document’ (Anonymous, 1994, p. 29). For the reviewer of ‘Sid’s Apartment’ , the cassette-tape no longer represented accessibility to sounds and sound recordings, but it did retain the stamp of originality, a kind of proof that the recordings really came from the artists themselves. In the end, the legacy of the cassette-tape was not that it liberated sound as much as further facilitated its privatization.

The Op legacy

In the short time since the advent of the battery-powered Sony Walkman in 1979, a range of new consumer technologies have emerged that allow people to create and listen to music in a variety of convenient ways, and each new technology prompts another round of corporate campaigns against music ‘pirating’ . Tape Op represents a new generation of sound engineers who wish to realize the potential of these technologies. The Portland, Oregon-based magazine pays homage to its ancestors in its name and a column titled ‘Under the Radar’ by Matt Mair Lowery, who reviews ‘homemade CD-Rs and cassettes’. In the Spring 2003 issue of Tape Op, Lowery reviewed three CDs; the first was ‘a collection of originals and traditional tunes’ recorded ina backyard shed; the second was an ‘honest recordingofsounds’,andthethirdconsistedof’reallypersonalsongs…cutright to a mono tape player’ (Lowery, 2003, p. 20). Lowery’s reviews suggest that the fascination with home recorded sound and the accompanying charm of homemade personal expression has anything but faded. Looking back at the history of the cassette-tape, it seems as if home recording technologies became popular precisely because they allowed anyone to ‘author’ music and therefore allowed people to claim slices of cultural material for their own under the guise of the self-inspired artist who worked with raw sounds to create unique singular productions. Such a perspective fails to see that recording artists had other options available, but chose to reinforce historical notions of authorship. Similarly, to read the eventual commercialization of the Pacific Northwest independent music scene as another example of corporate ‘co-optation’ is to fail to see how the mass culture the scene rejected created the very technological and conceptual conditions that made the scene possible. Such analysis can only conclude, as Scott Marshall does, that each new round of technological innovation results in the loss of a better form of communication. ‘[Cassette-tapes] were labors of love for ourselves, and for our friends in the cassette-net …we were all privy to a deeper and more personal, private, and inspiring aspect of communication’ (Marshall, 1995, pp. 212-14). The irony in Marshall’s encomium to the ‘International Cassette Underground’ is that corporations campaigned against home recording technologies because they diminished the viability of their recording rights and therefore eroded profits, while cassette-tape enthusiasts trumpeted those technologies as the answer to the corporatization of music because they allowed for the privatization of music. As Marshall himself puts it, the ‘thrill was in receiving a personally hand-crafted audio greeting card … Exchanging cassettes was like exchanging elaborate cultural calling-cards of information virus rather than consuming empty marketing commodity’ (Marshall, 1995, p. 112).

If the purpose of independent music practices is really to curb the homogenization and corporatization of everyday life, then an appeal to ‘author’ more texts is ineffective. The paradoxical nature of authorship suggests invention while it serves to constrain discursive anomalies; consequently, more authors do not result in a proliferation of musical ingenuity. If the home recording artists of today wish to recover the radical potential of recording technologies, they would do well to reconsider their investment in laying claim to a particular sound. Somewhere between recording rights, personal expression and anonymity lies a democratic musical sphere. It is for this reason that the Lost Music Network remains remarkable. For LMNOP, the only thing a proper name determined was in which edition of Op you were featured.

Notes

THE RESISTING MUSE

In 1984 Patrick Maley, then a student at The Evergreen State College, spent a recent inheritance on a Task-AM38 mixing board and other professional recording equipment. Other than the recording studio at Evergreen used by Bruce Pavitt, this was the only professional recording equipment in Olympia and, consequently, Maley’s launch of Yo-Yo Records marks a shift in the town’s independent music scene. According to Maley, up until that point, ‘people weren’t that interested in having really slick recording sounds necessarily; people would record a lot of stuff right into cassettes’ (2002, personal interview, 29 June).

As one Op reader put it, ‘That was the brilliant thing about LMNOP in that it granted authorship, it granted the status that goes with authorship, to everyone who ‘was capable of turning on a cassette recorder, and was brave enough then to bray into it whatever weird little sounds they could concoct’ (Fred Nemo, personal interview, 11 June 2002).

Chapter 13

Gothic music and the decadent individual Kimberley Jackson

You know, if more people understood what society is trying to hide, a lot less people would be inclined to try and recreate it – Ian Curtis (quoted in Thompson, 2002, p.42).

Because of its associations with punk and the music of rebellion, on the one hand, and its subcultural cohesion on the other, discussions of late twentieth-century gothic music most often centre on the themes of assimilation and identity. In his edited collection entitled Gothic: Transmutations of Horror in Late Twentieth Century Art, Christoph Grunenberg writes of contemporary Gothicism that ‘at the end of mainstream appropriation inevitably stood commercial exploitation and semantic exhaustion, reducing stylistic idioms to innocuous mass-market caricatures devoid of their original subversive power and meaning’ (Grunenberg, 1997, p. 173). Joshua Gunn, in his article ‘Marilyn Manson is not Goth: Memorial Struggle and the Rhetoric of Subcultural Identity’ (1999b), would include such statements as Grunenberg’s in what he calls ‘the assimilation thesis’. Gunn argues, using the ‘Goth’ subculture as his model, that there is a fecund relationship between, on the one hand, what is assimilable, or what has been assimilated, of a subculture (including misconceptions and misrepresentations) into the ‘mainstream’ and, on the other hand, what remains only within the ‘memory’ of the subculture itself – relationship that is often antagonistic. Gunn wishes to employ this site of antagonism to show how ‘both popular representations of the subculture and the thoughts of goths themselves are needed for an analysis of their dynamic interaction in the creation of individual and community identities’ (Gunn, 1999b, p. 409). While Gunn’s analysis offers us access to what is still vital and ‘dynamic’ in the negotiations of identity taking place between the subculture and the mainstream, it is my intention to highlight the characteristics of gothic music prior to its creating a ‘SUbculture’ and to describe a point of radical disjunction at the site of emergence of this particular form of Gothicism. In theories of gothic music, and within the gothic subculture itself, the violence of this site of emergence has been forgotten. This forgetting was perhaps necessary if there was to be any ‘memory’, subcultural or otherwise, to inform a determinate ‘scene’, since what is revealed when one looks closely at the beginnings of this musical form is a movement

Other pUblications continued to support cassette-based recordings such as Massachusetts-based Cassettera; Gajoob, a Salt Lake City publication with connections to a radio show, and Kentucky Fried Royalty, ‘a non-profit world-wide independent cassette tape distribution network’, located in California (Sound Choice, Wroter 1990, p. 11).

These logics did not hinge on musical virtuosity. A mode of perception developed that allowed for distinctions between good awfulness and bad awfulness. The memb~rs of Beat Happening, for example, had little working knowledge of their instruments, but at some point listeners learned to appreciate this lack of skill as a kind of skill in and of itself (Azerrad, 2001).

Snipehunt featured a ‘Top 69’ list of bands in every issue. This particular review is of the cassette-tape version of ‘Welcome’, which was also available in vinyl. The cassette-tape medium in this case holds no particular significance.